Your body language may shape who you are | Amy Cuddy | TED

Summary

TLDR本文探讨了肢体语言对个人心理和生理状态的影响。演讲者Amy Cuddy通过研究发现,采取高权力姿态的人在两分钟内,其荷尔蒙水平发生变化,能够更加自信、乐观,而低权力姿态则导致相反效果。她鼓励人们在面对压力情境时,通过简单的肢体调整来提升自我感知的力量,从而改善生活结果。

Takeaways

- 🧍♂️ 改变姿势两分钟可以显著影响你的生活,提升自信和改善生活结果。

- 🔍 人们非常关注身体语言,尤其是他人的身体语言,它在社交互动中起着重要作用。

- 🤝 握手等非语言行为可以影响人们对他人的看法,甚至影响重要的生活决策。

- 🧐 社会科学家研究显示,人们通过观察他人的身体语言来判断对方,这可能预测重要的生活结果。

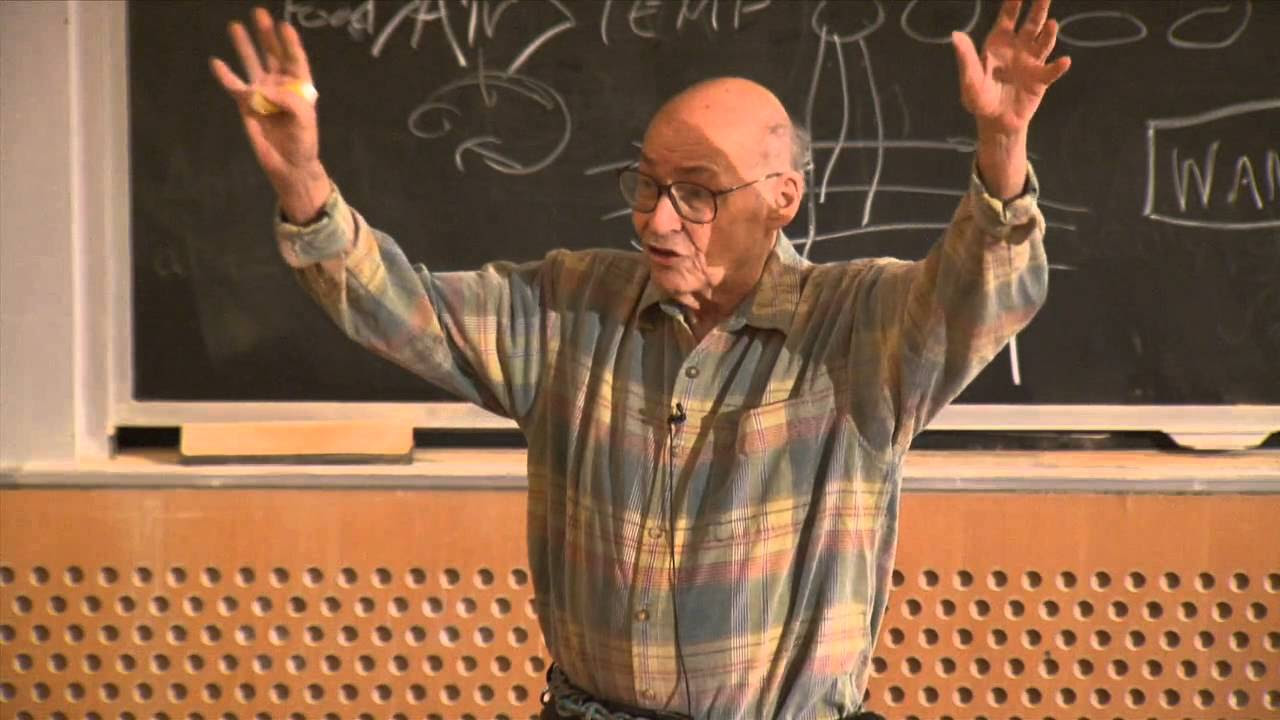

- 💪 权力和支配的非语言表现通常与扩张有关,如占据空间和展开身体。

- 🤗 感到无力时,人们倾向于收缩身体,减少自己的存在感。

- 👩🏫 在MBA课堂中,学生的非语言行为与他们的参与度和成绩相关联。

- 🤔 研究表明,假装拥有某种感觉,如力量感,实际上可以导致真正感受到这种感觉。

- 🧬 权力感与两种关键激素有关:睾丸素(支配激素)和皮质醇(压力激素)。

- 📈 实验表明,采取高权力姿势的人在风险承受、睾丸素水平和皮质醇水平上都有积极变化。

- 🚀 即使是短时间的高权力姿势也能在压力情境下改善个人的表现和自我感受。

- 🌟 最后,演讲者鼓励人们在面临压力时尝试力量姿势,并分享这一科学发现,以帮助那些缺乏资源的人。

Q & A

演讲者提供了一个什么样的生活小技巧来改善我们的身体语言?

-演讲者提供了一个简单的生活小技巧,即改变我们的姿势两分钟,这可能会显著改变我们的生活。

为什么演讲者建议我们在演讲开始前先进行一次身体姿势的自我检查?

-演讲者建议我们进行身体姿势的自我检查,以意识到我们可能在无意识中采取了让自己显得更小的姿势,比如弯腰、交叉双腿或抱臂,这可能会影响我们的自信和他人对我们的看法。

演讲者提到了哪些非语言行为对我们的判断和生活结果有重大影响?

-演讲者提到了握手、面部表情、在线表情符号的使用等非语言行为,这些行为会影响我们对他人的判断,甚至可能预测重要的生活结果,如工作聘用或晋升、约会邀请等。

Nalini Ambady的研究显示了什么?

-Nalini Ambady的研究表明,当人们观看30秒无声的医生与病人互动视频时,他们对医生友好程度的判断可以预测该医生是否会被起诉。

Alex Todorov的研究揭示了什么?

-Alex Todorov的研究揭示了人们在仅仅一秒钟内对政治候选人面部表情的判断,可以预测70%的美国参议院和州长竞选结果。

为什么我们的非语言行为对我们自己也有影响?

-我们的非语言行为不仅影响他人对我们的看法,也影响我们自己的心理和生理状态。例如,当我们采取扩张性的姿势时,我们可能会感到更有力量和自信。

演讲者如何定义权力和支配的非语言表达?

-演讲者定义权力和支配的非语言表达为扩张性的姿势,比如让自己显得更大、伸展身体、占据空间,这在动物界和人类中都是相同的。

演讲者提到了哪些与权力相关的性别差异?

-演讲者提到,在MBA课堂上,女性比男性更可能采取让自己显得更小的姿势,这可能与女性长期感到的权力感较低有关。

演讲者和Dana Carney进行的实验是关于什么的?

-演讲者和Dana Carney进行的实验是关于人们是否可以通过采取高权力姿势或低权力姿势两分钟来改变他们的荷尔蒙水平,从而影响他们的行为和感受。

实验结果表明,采取高权力姿势的人在哪些方面发生了变化?

-实验结果表明,采取高权力姿势的人在风险承受能力、睾酮水平和皮质醇水平方面发生了积极的变化,他们更愿意参与赌博,感到更有力量。

演讲者如何建议我们利用这些发现来改善我们的生活?

-演讲者建议我们在面临评估性或社会威胁性的情况时,比如工作面试,可以尝试采取高权力姿势两分钟,以帮助我们调整心态,提高自信,减少压力反应。

演讲者分享了她个人的一个什么经历来说明'fake it till you become it'的观点?

-演讲者分享了她19岁时遭遇严重车祸后,智商下降,感到无力和像个骗子一样的经历。她通过不断努力和'fake it till you become it'的方式,最终在学术上取得了成功。

演讲者为什么鼓励我们分享这个发现?

-演讲者鼓励我们分享这个发现,因为这是一个简单且不需要任何资源或技术的方法,对于那些没有资源、技术、地位和权力的人来说,它可以在私下里显著改变他们的生活结果。

Outlines

此内容仅限付费用户访问。 请升级后访问。

立即升级Mindmap

此内容仅限付费用户访问。 请升级后访问。

立即升级Keywords

此内容仅限付费用户访问。 请升级后访问。

立即升级Highlights

此内容仅限付费用户访问。 请升级后访问。

立即升级Transcripts

此内容仅限付费用户访问。 请升级后访问。

立即升级5.0 / 5 (0 votes)