Xolobeni - The Right To Say No

Summary

TLDRThe script narrates the struggle of a South African community against an Australian mining company's plans to exploit their coastal land. The community, led by the Amadiba Crisis Committee, fights for their right to say no to mining, which threatens their livelihood and environment. Despite government support for the project, the community seeks sustainable development through tourism and agriculture, emphasizing the importance of land for their future generations.

Takeaways

- 🌍 The community's deep connection to the land is threatened by a mining company's plans to exploit the area.

- 🚫 The locals have been resisting the mining project for over twenty years, prioritizing their traditional way of life over potential short-term economic gains.

- 🐏 Livestock and natural resources are central to the community's livelihood, and they fear the mining activities will disrupt these essential elements.

- 🗣️ The community has voiced their concerns about the mining project's potential to destroy their environment and way of life.

- 🤝 The Caruso brothers' promises of jobs, clinics, and infrastructure did not sway the community, who values their current lifestyle and environment.

- 🏛️ The community's decision-making takes place at Komkhulu, their traditional court, where they collectively reject the mining proposal.

- 🏞️ The community seeks sustainable development through tourism and agriculture, rather than environmentally damaging mining.

- 🏦 The community's struggle is against a backdrop of South African history, where mining has often come at the expense of black communities.

- 🏅 A significant legal victory was achieved when the courts recognized the community's right to consent and to say no to mining projects.

- 🛣️ The proposed highway, claimed to connect communities, is suspected to actually serve the mining company's interests, further dividing the community.

- ⚖️ Despite legal victories, the government's appeal and the mining company's persistence indicate a continued struggle for the community.

Q & A

What is the main conflict described in the transcript?

-The main conflict is between a community in South Africa and an Australian minerals company that wants to mine in a beautiful coastal area, which the community relies on for their livelihood and well-being.

What promises did the minerals company make to the community?

-The company promised to create jobs, build clinics, hospitals, and better roads, and provide clean water for the community.

Why did the community reject the company's promises?

-The community rejected the promises because they were concerned about the potential negative impact on their livestock, water, and the plants they use for healing, fearing it would disturb their way of living.

What is the significance of Komkhulu in the community's struggle?

-Komkhulu is a traditional court where the community discusses local issues and makes decisions regarding land. It represents the community's power and autonomy in decision-making.

How did the community attempt to address the mining issue?

-The community formed the Amadiba Crisis Committee, reported the issue to the police and municipality, and eventually sought legal help to assert their right to consent to mining activities.

What was the outcome of the court case mentioned in the transcript?

-The court recognized the community's residual right of consent for mining activities, affirming that power belongs to the people and not just traditional leaders or the government.

Why did the government appeal the court's decision?

-The government appealed the decision because they wanted to grant mining rights to the Australian company, despite the community's opposition.

What was the community's reaction to the government's appeal?

-The community was surprised and disappointed that their own government would appeal against them, questioning their right to decide what is best for their community.

What is the community's vision for development in their area?

-The community prefers sustainable development, such as tourism and agriculture, rather than mining, which they believe would destroy their land and way of life.

How does the community view the proposed highway project?

-The community sees the highway project as a means to support the mining company rather than connect their communities, and they worry it will split their community and lead to dependence on the state.

What is the community's stance on the mining company's presence and operations?

-The community is determined to continue fighting against the mining company's operations, even if it means taking the fight to the Constitutional Court, as they believe the decision ultimately lies with them.

Outlines

Cette section est réservée aux utilisateurs payants. Améliorez votre compte pour accéder à cette section.

Améliorer maintenantMindmap

Cette section est réservée aux utilisateurs payants. Améliorez votre compte pour accéder à cette section.

Améliorer maintenantKeywords

Cette section est réservée aux utilisateurs payants. Améliorez votre compte pour accéder à cette section.

Améliorer maintenantHighlights

Cette section est réservée aux utilisateurs payants. Améliorez votre compte pour accéder à cette section.

Améliorer maintenantTranscripts

Cette section est réservée aux utilisateurs payants. Améliorez votre compte pour accéder à cette section.

Améliorer maintenantVoir Plus de Vidéos Connexes

DAIRI DIANCAM TAMBANG

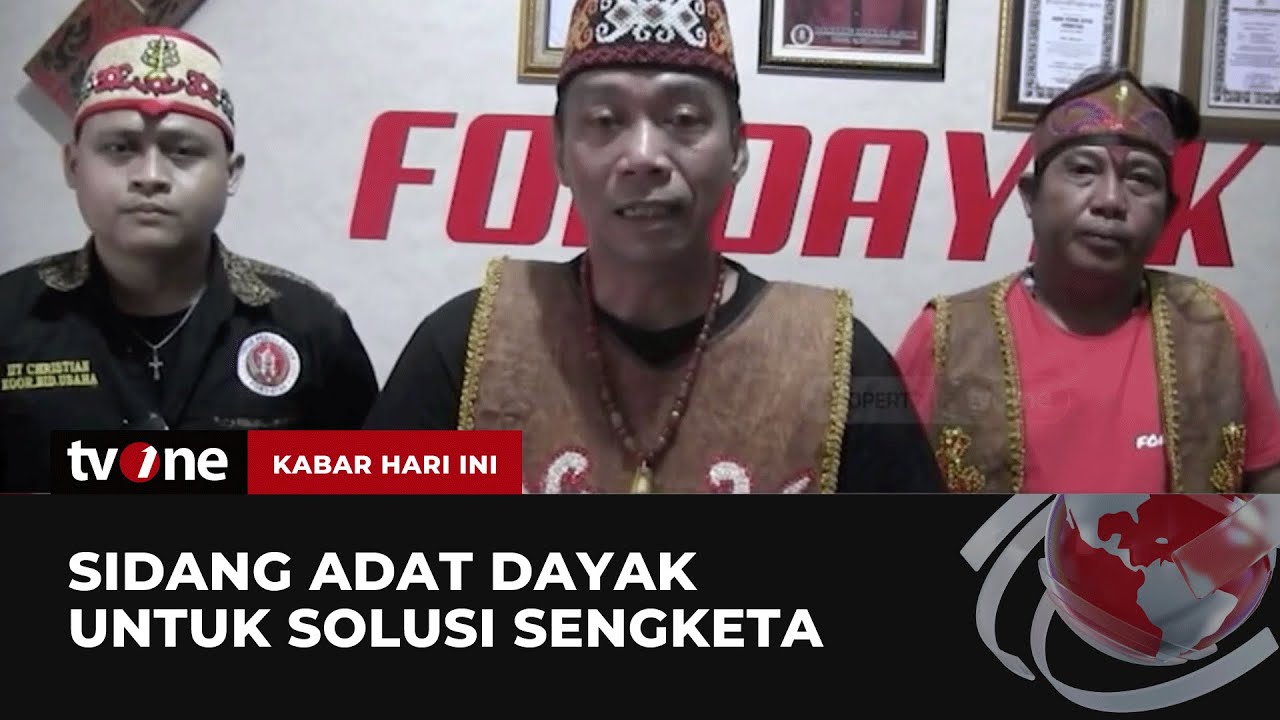

Warga Ajukan Sidang Adat Dayak Untuk Selesaikan Sengketa Lahan Tambang | Kabar Hari Ini tvOne

Penyelesaian Konflik Sengketa Tanah Hak Ulayat Suku Dayak Kampung 10 Upau Dengan PT Adaro Indonesia

Land Grabs

Indonesia Calling by Joris Ivens 1946 - Indonesian Subtitle

LOS DRAGONES DE LAS GALAPAGOS

5.0 / 5 (0 votes)