The Humans That Lived Before Us

Summary

TLDRThe script delves into the early Pleistocene Epoch, exploring the evolutionary journey of hominins, particularly Homo habilis. It discusses the debate over whether Homo habilis should be classified within the Homo genus due to its mix of primitive and advanced traits, such as tool use and bipedalism. The narrative also touches on the discovery of Australopithecus sediba and Homo rudolfensis, and the challenges in defining what it means to be 'human'. It highlights the complexity of human evolution, with Homo erectus emerging as an indisputable member of the Homo genus, contrasting with the taxonomic uncertainty surrounding Homo habilis.

Takeaways

- 🕵️♂️ The early Pleistocene Epoch, from about 2.4 million to 1.4 million years ago, was a significant period for hominin evolution in southern and eastern Africa.

- 🧠 Homo habilis, meaning 'handy man', was one of the early hominins with a slightly larger brain and smaller teeth compared to australopithecines, and is known for possibly making and using stone tools.

- 🤔 The classification of Homo habilis within the genus Homo has been debated due to the discovery of similar traits in other hominin species like australopithecines.

- 🌳 The definition of what constitutes a member of the genus Homo has evolved over time, with criteria such as bipedalism, brain size, and tool use being reconsidered.

- 🦶 The Laetoli footprints and Lucy's skeleton provided evidence that upright walking and certain limb proportions were not exclusive to Homo, complicating the definition of the genus.

- 🧬 Australopithecus sediba and Homo rudolfensis are other hominin species that have been considered for inclusion in the genus Homo due to their Homo-like traits.

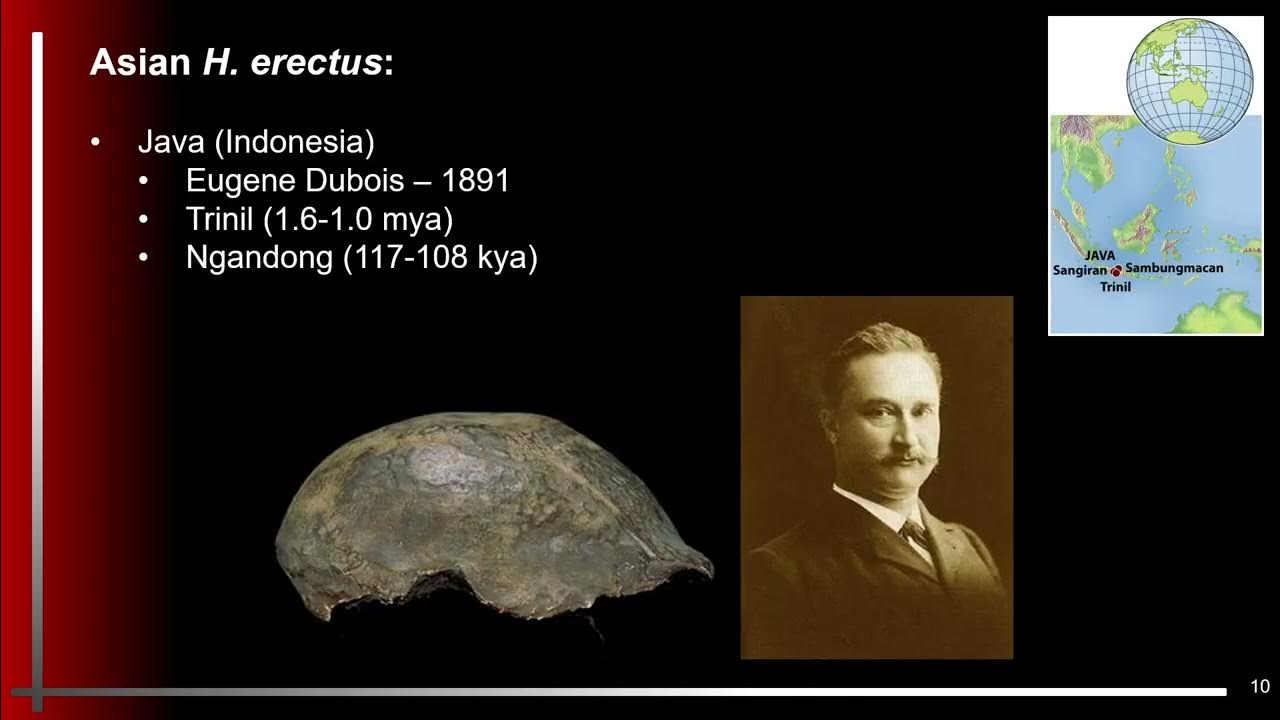

- 🌏 Homo erectus is recognized as the first member of the genus Homo to have migrated out of Africa, with evidence found as far as China and Indonesia.

- 🏞️ The variation in fossils found at Dmanisi, Georgia, has led some researchers to suggest that early Homo species might be better classified as a single species, Homo erectus.

- 🔍 The search for defining features of the genus Homo continues, with new criteria such as tooth size and developmental pace being considered.

- 🌿 The debate over the classification of Homo habilis reflects the broader challenges in defining the Homo genus and what it means to be 'human' in the context of our evolutionary history.

Q & A

What is the significance of the early Pleistocene Epoch for hominins?

-The early Pleistocene Epoch, from about 2.4 million to 1.4 million years ago, was a period of significant evolutionary development for hominins, with various branches flourishing across southern and eastern Africa.

What are the key features of Homo habilis?

-Homo habilis, meaning 'handy man,' was a hominin species characterized by a height of over a meter, a slightly larger brain, smaller teeth compared to australopithecines, and the ability to make and use stone tools.

Why is the classification of Homo habilis within the genus Homo debated?

-The classification of Homo habilis within the genus Homo is debated because subsequent discoveries of similar traits in other hominin species, such as australopithecines, have blurred the distinctiveness of Homo habilis, leading to questions about its unique place within the genus.

What is the importance of the Laetoli footprints in understanding hominin evolution?

-The Laetoli footprints, dating back more than a million years, provide evidence that hominins were bipedal before Homo habilis, challenging the notion that bipedalism was exclusive to the genus Homo.

What are lifestyle adaptations and how do they relate to defining the genus Homo?

-Lifestyle adaptations refer to features linked to how a hominin lived, such as diet, mobility, and habitat. They are considered in defining the genus Homo because they reflect the evolutionary changes in hominin behavior and ecology.

What criteria were proposed for a hominin to be classified within the genus Homo?

-Criteria proposed for classification within Homo included an adult brain size greater than 600 cubic centimeters, limb proportions similar to Homo sapiens, the use of language, and the manufacture and use of stone tools.

Why is the specimen KNM-ER 1813 significant in the discussion about Homo habilis?

-The specimen KNM-ER 1813, with a cranial capacity of only 510 ccs, challenges the brain size criterion for genus Homo, as it is smaller than the proposed 600cc threshold.

Who are some other hominin species that lived alongside Homo habilis during the early Pleistocene?

-Other hominin species that lived alongside Homo habilis include Australopithecus sediba and Homo rudolfensis, both of which exhibit traits that blur the lines of classification within the genus Homo.

What is the significance of Homo erectus in the human evolutionary timeline?

-Homo erectus is significant as it is one of the first indisputable members of the genus Homo, with a wide geographical distribution and traits much more similar to modern humans, including a larger brain and modern human-like proportions.

What is the current status of Homo habilis in terms of its classification within the genus Homo?

-Homo habilis remains a taxon in limbo, with no consensus on its classification. Some experts propose it be reclassified within Australopithecus, while others suggest it deserves its own genus.

What new criteria are being considered for defining the genus Homo?

-New criteria being considered for defining the genus Homo include tooth size, which may indicate diet quality and food preparation, and the pace of development, which is reflected in the extended childhood and adolescence periods in modern humans.

Outlines

Esta sección está disponible solo para usuarios con suscripción. Por favor, mejora tu plan para acceder a esta parte.

Mejorar ahoraMindmap

Esta sección está disponible solo para usuarios con suscripción. Por favor, mejora tu plan para acceder a esta parte.

Mejorar ahoraKeywords

Esta sección está disponible solo para usuarios con suscripción. Por favor, mejora tu plan para acceder a esta parte.

Mejorar ahoraHighlights

Esta sección está disponible solo para usuarios con suscripción. Por favor, mejora tu plan para acceder a esta parte.

Mejorar ahoraTranscripts

Esta sección está disponible solo para usuarios con suscripción. Por favor, mejora tu plan para acceder a esta parte.

Mejorar ahora5.0 / 5 (0 votes)