How I Teach Kids to Love Science | Cesar Harada | TED Talks

Summary

TLDRCesar Harada shares his journey from childhood curiosity to educating the next generation on environmental issues. He discusses the reality of plastic pollution, oil spills, and nuclear contamination, and how he involves his students in innovative solutions. From building robots to detect ocean plastics to developing spectrometry prototypes for water quality, Harada emphasizes the importance of empowering young minds to tackle global challenges, fostering a future of citizen scientists and inventors.

Takeaways

- 🌍 The speaker emphasizes the importance of freedom with responsibility, learned from childhood experiences.

- 🏖️ As an adult, the speaker teaches citizen science and invention, highlighting the issue of plastic pollution in oceans.

- 👨🎓 The speaker's students, aged six to fifteen, are engaged in inventing solutions for environmental problems.

- 🔬 The class transformed into a workshop to create a workbench for prototyping, emphasizing hands-on learning.

- 🤖 The students aimed to invent a better way to collect data on plastic pollution using robots and rapid prototyping.

- 🌊 They developed a floating robot to capture images of plastic particles in water, demonstrating innovative problem-solving.

- 🔬 The students also built a spectrometer to analyze water quality, showing adaptability in scientific exploration.

- 🌏 The project's scope expanded from local to global issues, including oil spills and radioactivity from Fukushima.

- 📈 The speaker and students created a topographical map to understand and visualize radioactivity dispersion.

- 🧪 They collected seabed sediment to measure radioactivity, contributing to the safety of local communities and the environment.

- 🌱 The speaker calls for honesty with children about environmental issues, urging the use of their imagination to invent solutions.

Q & A

What is the main message the speaker wants to convey about responsibility and freedom?

-The speaker emphasizes that freedom comes with responsibility, as illustrated by their childhood experience of being told to clean up after themselves. This theme is carried into adulthood, where they note that adults often make a mess but are not good at cleaning it up, suggesting a broader societal responsibility.

What is the speaker's profession and where does he teach?

-The speaker is a teacher who teaches citizen science and invention at the Hong Kong Harbour School.

Why do the students clean up the beaches?

-The students clean up the beaches as part of their role as good citizens, after discovering piles of trash on the beaches during their walks.

What percentage of the oceans have plastic in them according to the speaker?

-According to the speaker, more than 80 percent of the oceans have plastic in them.

How do the students and the speaker approach the problem of plastic pollution?

-The students and the speaker approach plastic pollution by inventing a better way to collect data on plastic in the oceans. They build a floating robot that captures images of plastic pieces and processes them to estimate the amount of plastic in the water.

What is 'rapid prototyping' as mentioned in the script?

-Rapid prototyping refers to the quick process of creating a rough model or prototype of an invention. In the script, it is used to describe the fast and iterative process of building and testing their inventions, such as turning table lamps and webcams into parts of a floating robot.

How did the students become aware of the oil spill problem in the Sundarbans?

-The students became aware of the oil spill problem in the Sundarbans through the internet and news, where they saw an image of a child cleaning up an oil spill bare-handed.

What technology did the students use to help address the oil spill problem?

-The students used a technology called spectrometry to help address the oil spill problem. They built a prototype of a spectrometer to identify substances in the water.

Why did the speaker and the students want to measure radioactivity in Fukushima?

-The speaker and the students wanted to measure radioactivity in Fukushima to understand the extent of contamination from the nuclear power plant after the 2011 earthquake and tsunami, and to contribute to the safety of the local population and the environment.

What is the significance of the mega-space the speaker mentions at the end?

-The mega-space is significant because it is a large industrial site in Hong Kong that has been transformed into a space focused on social and environmental impact. It provides a place where adults and kids can collaborate, invent, and create solutions for various problems using a wide range of materials and technologies.

What is the speaker's view on shielding children from the 'ugly truth'?

-The speaker believes that we can no longer afford to shield children from the 'ugly truth' because their imagination and creativity are needed to invent solutions to the world's problems.

Outlines

此内容仅限付费用户访问。 请升级后访问。

立即升级Mindmap

此内容仅限付费用户访问。 请升级后访问。

立即升级Keywords

此内容仅限付费用户访问。 请升级后访问。

立即升级Highlights

此内容仅限付费用户访问。 请升级后访问。

立即升级Transcripts

此内容仅限付费用户访问。 请升级后访问。

立即升级浏览更多相关视频

TUGAS SOSIOLOGI KELOMPOK 6 PEMBERDAYAAN KOMUNITAS GENRE DI KABUPATEN PRINGSEWU

Breaking Generational Cycles of Trauma | Brandy Wells | TEDxKingLincolnBronzeville

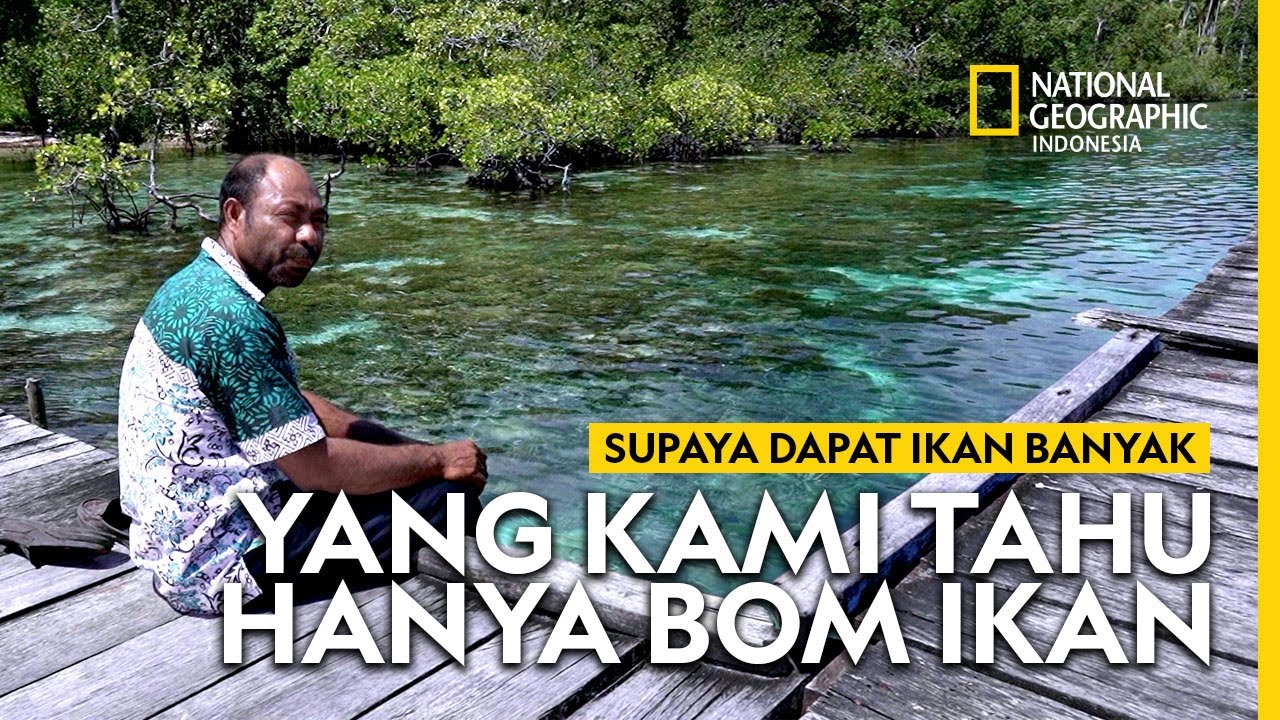

Simak Pelajaran penting dari Raja Ampat yang tak terlupakan

¿Cómo acercar el saber tradicional al académico? I Fuerza Latina DW

Why Pepe Herrera Left The Country and Quit Showbiz For A While | Toni Talks

DULU JADI TUKANG PERAWATAN MESIN KINI JADI PENGUSAHA HEBAT DI BALI❗

5.0 / 5 (0 votes)