Public Debt: how much is too much?

Summary

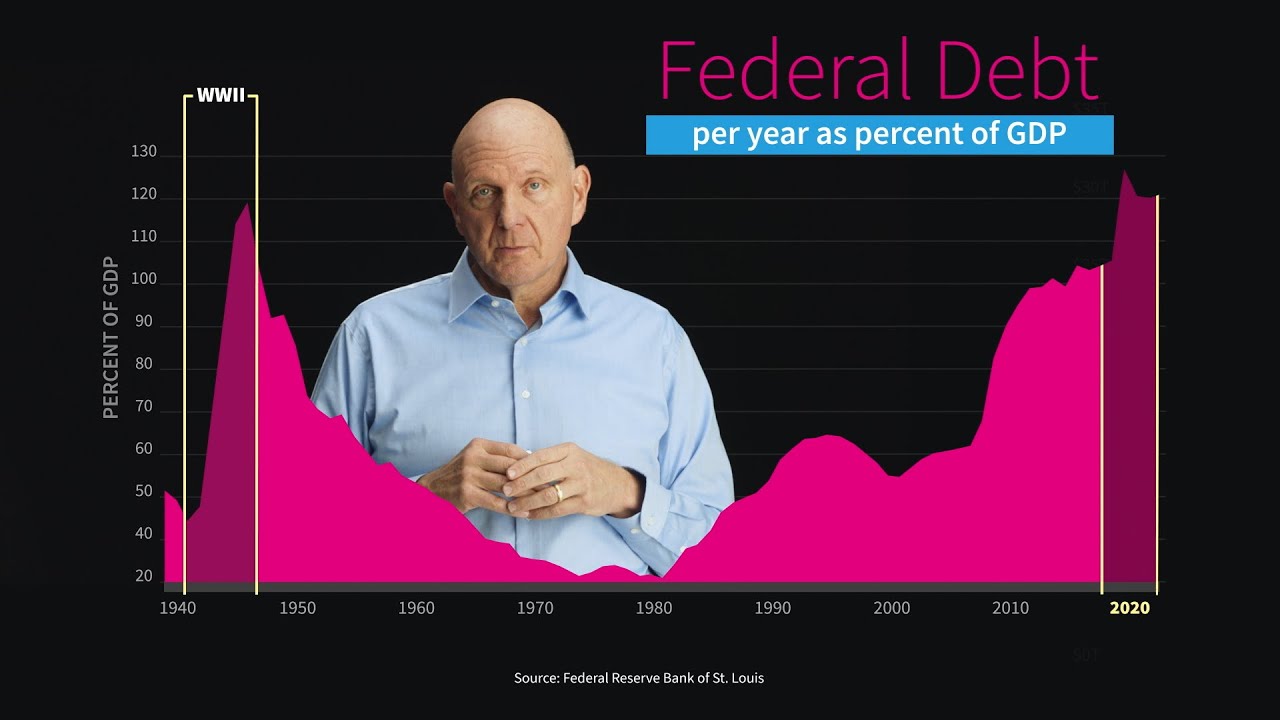

TLDRThe COVID-19 pandemic has led to unprecedented levels of government borrowing, with the US alone borrowing $3 trillion in Q2 2020. Historically, high debt post-war periods like after Napoleonic wars and WWII were managed, and recent economic thinking suggests that higher debt levels may be sustainable, especially with low-interest rates and growing economies. However, the sustainability of such debt is uncertain, and the pandemic's impact on public debt will be a significant legacy, with risks including potential rises in interest rates.

Takeaways

- 🌐 The COVID-19 pandemic has led to governments worldwide borrowing and spending at unprecedented rates.

- 💵 Between April and June, the United States alone borrowed a record $3 trillion, the most ever in a single quarter.

- 📈 The rise in public debt has been dramatic and unlike anything seen in recent history.

- 🏛️ Historically, governments have borrowed heavily to finance wars and to stabilize economies.

- 💼 To finance spending, governments issue bonds, which are essentially IOUs repaid over time with interest.

- 🌍 Government bonds are considered safe assets and are bought by a variety of investors, including foreign governments.

- 📉 After World War II, governments were cautious about borrowing due to high debts, but this changed with the global financial crisis.

- 📊 The economic downturn following the financial crisis led to a rise in public debt in both rich and emerging economies.

- 💡 New economic thinking, influenced by Olivier Blanchard, suggests that governments can sustain higher levels of debt than previously thought.

- 🌟 As long as GDP growth outpaces debt interest accumulation, countries can effectively grow out of debt without fiscal strain.

- 🚨 Despite the potential for higher debt sustainability, there are risks, including the possibility of rising interest rates.

Q & A

What was the unprecedented rate of borrowing by the U.S. between April and June?

-Between April and June, the United States borrowed $3 trillion, which is the largest amount borrowed in a single quarter since records began.

What is the historical context of public debt levels after major conflicts?

-Historically, after the Napoleonic wars in 1815, Britain's debt was 164% of GDP, and after World War II, it was even higher at 259% of GDP.

Why have governments traditionally issued bonds?

-Governments have traditionally issued bonds to raise money, which are essentially IOUs repaid over a fixed term with interest, depending on the bond's length.

Who are the typical buyers of government bonds?

-Government bonds are bought by various investors including pension funds, hedge funds, banks, individual investors, a country's own central bank, local government, and foreign governments.

Why are U.S. government bonds considered safe assets?

-U.S. government bonds are considered safe assets because the U.S. government is typically reliable in repaying its debts, ensuring investors get their money back.

What was the impact of the 1970s borrowing on inflation according to the script?

-In the 1970s, high levels of government borrowing were blamed for high inflation, as the additional money in the economy was too much for it to absorb, leading to increased prices.

How did the global financial crisis affect public debt levels in rich and emerging economies?

-In the decade following the global financial crisis, public debt in rich countries rose from 74% to around 105% of GDP, and in emerging economies it rose from roughly 35% to 48% of GDP.

What was the lesson learned from austerity measures following the financial crisis?

-The lesson learned was that austerity in a time of economic weakness can hurt economies so much that it doesn't do any good, as the economy becomes too weak to generate sufficient tax revenues.

What did Olivier Blanchard argue in his 2019 speech about government borrowing?

-Olivier Blanchard argued that governments could borrow far more than previously believed, as long as GDP growth outpaces debt accumulation and additional borrowing is controlled.

How has the coronavirus pandemic affected government borrowing?

-The coronavirus pandemic led to the greatest exercise in public borrowing for generations, with governments borrowing unprecedented amounts to support their economies.

What are the risks associated with the current low interest rates on government bonds?

-The risks include the possibility that interest rates could rise again, which would put countries with high debt in trouble. Additionally, the cause of low interest rates is not entirely understood, which introduces uncertainty about their future.

Outlines

This section is available to paid users only. Please upgrade to access this part.

Upgrade NowMindmap

This section is available to paid users only. Please upgrade to access this part.

Upgrade NowKeywords

This section is available to paid users only. Please upgrade to access this part.

Upgrade NowHighlights

This section is available to paid users only. Please upgrade to access this part.

Upgrade NowTranscripts

This section is available to paid users only. Please upgrade to access this part.

Upgrade NowBrowse More Related Video

5.0 / 5 (0 votes)