Wilfred Owen: 'Exposure' - Mr Bruff Analysis

Summary

TLDRThis video script offers an in-depth analysis of Wilfred Owen's poem 'Exposure', focusing on its rhyme scheme, pararhyme, refrain, personification, sibilants, religious imagery, intertextual references, caesura, and more. It explores Owen's background, the poem's context within WWI, and its powerful depiction of soldiers' suffering and the futility of war. The analysis also discusses the poem's structure, highlighting the contrast between intense anticipation and the ultimate letdown of 'nothing happening', reflecting the soldiers' experience of waiting in vain.

Takeaways

- 📜 'Exposure' is considered Wilfred Owen's most polished and impressive poem, reflecting his extensive drafting and redrafting efforts.

- 🎨 The poem utilizes various poetic techniques such as rhyme scheme, pararhyme, refrain, personification, sibilants, religious imagery, intertextual references, and caesura.

- 🖋️ Owen's biographical background, including his initial pursuit of a church career and his admiration for John Keats, influenced his poetry.

- 🌐 'Exposure' is set against the backdrop of World War I, challenging the romanticized views of war prevalent before Owen's time.

- ❄️ The poem focuses on the harsh weather conditions faced by soldiers in the trenches, emphasizing the war between soldiers and nature rather than between soldiers themselves.

- 🔄 Owen employs a repetitive structure in 'Exposure' to reflect the soldiers' ongoing, futile wait for action amidst the trenches.

- 🔁 The rhyme scheme 'ABBAC' and the use of pararhyme contribute to a sense of incompleteness and tension, mirroring the soldiers' experiences.

- 🔊 The poem's refrain 'but nothing happens' underscores the futility and stagnation of trench warfare.

- 🌉 Owen's use of intertextual references, particularly to John Keats' 'Ode to a Nightingale', contrasts the joy of nature in Keats' work with the horrors faced by soldiers in war.

- 🏠 The poem's ending, which loops back to its beginning, reinforces the theme of futility and the lack of resolution in the soldiers' suffering.

Q & A

What is the main focus of the analysis in the video script?

-The main focus of the analysis is on Wilfred Owen's poem 'Exposure', with particular attention to its rhyme scheme, pararhyme, refrain, personification, sibilants, religious imagery, intertextual references, caesura, and more.

What are some of the poetic techniques discussed in the script?

-The script discusses techniques such as rhyme scheme, pararhyme, refrain, personification, sibilants, religious imagery, intertextual references, and caesura.

Why is 'Exposure' considered Wilfred Owen's most polished poem?

-'Exposure' is considered Wilfred Owen's most polished poem because he spent a significant amount of time drafting and redrafting it, resulting in a rich and complex work.

What is the significance of the poem's title 'Exposure'?

-The title 'Exposure' refers not only to the exposure to harsh weather conditions and the threat of enemy soldiers but also symbolizes the exposure of the truth about the reality of war to the British public.

What is the role of the weather in 'Exposure'?

-In 'Exposure', the weather is portrayed as a more significant threat than enemy soldiers, with the poem highlighting the soldiers' suffering due to the cold and snow.

How does Wilfred Owen's background influence his poetry?

-Owen's background, including his initial pursuit of a career in the church and his admiration for John Keats, influenced his poetry by imbuing it with a sense of moral conflict and a deep appreciation for poetic craft.

What is the significance of the refrain 'but nothing happens' in the poem?

-The refrain 'but nothing happens' emphasizes the futility and stagnation of war, as well as the soldiers' constant state of alertness with no resolution or action.

How does the rhyme scheme 'ABBAC' contribute to the poem's theme?

-The 'ABBAC' rhyme scheme contributes to the poem's theme by reflecting the anticipation and unfulfilled expectations of battle, with the final line breaking the pattern to mirror the lack of resolution in the soldiers' experiences.

What is the role of intertextual references in 'Exposure'?

-Intertextual references in 'Exposure', such as those to John Keats' 'Ode to a Nightingale', serve to highlight contrasts between Owen's war experiences and the Romantic idealization of nature, emphasizing the harsh realities of war.

What is the effect of personification in the poem?

-Personification in 'Exposure' gives human characteristics to the weather, emphasizing its deadliness and creating a sense of war between the soldiers and nature.

How does the use of sibilance in 'Exposure' contribute to its atmosphere?

-Sibilance, through the repetition of 'ss' and 'sh' sounds, creates a hissing sound that evokes a sense of danger and unease, mirroring the constant threat faced by the soldiers.

Outlines

This section is available to paid users only. Please upgrade to access this part.

Upgrade NowMindmap

This section is available to paid users only. Please upgrade to access this part.

Upgrade NowKeywords

This section is available to paid users only. Please upgrade to access this part.

Upgrade NowHighlights

This section is available to paid users only. Please upgrade to access this part.

Upgrade NowTranscripts

This section is available to paid users only. Please upgrade to access this part.

Upgrade NowBrowse More Related Video

Solitude - Poem Analysis

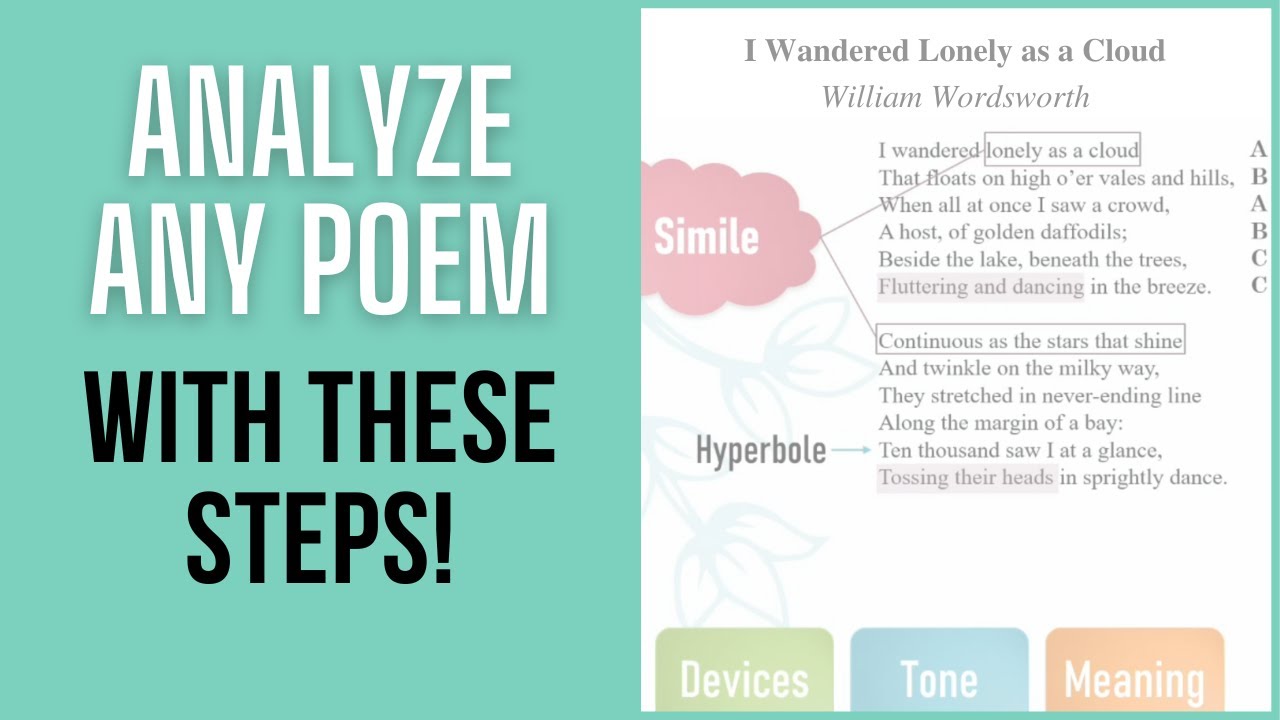

Analyze ANY Poem With These Steps!

'Exposure' by Wilfred Owen in 5 Minutes: Quick Revision

Analisis puisi unsur fisik dan unsur bathin Gadis peminta-minta#puisi#canva

Unsur Intrinsik Puisi: Video Pembelajaran Sastra Kelas X berisi Analisis Puisi Bahasa Indonesia

Anthem For Doomed Youth - Ten Minute Teaching

5.0 / 5 (0 votes)