Why is pi here? And why is it squared? A geometric answer to the Basel problem

Summary

Please replace the link and try again.

Takeaways

- 😀 Euler's solution to the Basel problem, after 90 years, reveals that the sum of the inverses of square numbers approaches pi squared divided by 6.

- 🤔 The Basel problem involves summing the inverses of square numbers (1 + 1/4 + 1/9 + 1/16 + ...) and discovering that this infinite series equals pi squared over 6.

- 🔍 Pi's appearance in the Basel problem is surprising, as pi is often tied to circles, and its squared form shows a deeper, unexpected connection.

- 💡 The script introduces the concept of 'apparent brightness' of light sources to help explain the Basel problem, framing it with the idea of lighthouses spaced on a number line.

- 🌐 The inverse square law is key to understanding how light spreads and why the sum of the inverses of squares corresponds to pi squared divided by 6.

- 💡 The inverse square law applies to all point-source phenomena (e.g., light, sound, heat) where intensity diminishes with the square of the distance.

- 🧑🏫 The inverse Pythagorean theorem is introduced as a way to transform a single lighthouse into two without altering the total brightness the observer experiences.

- 🔄 Through a series of geometric transformations, the script demonstrates how the apparent brightness remains constant while rearranging the positions of the lighthouses.

- ⚙️ The core idea involves expanding circles with increasing radii and evenly spaced lighthouses, which results in a series that converges to pi squared divided by 4, an essential step in solving the Basel problem.

- 🌍 A visual and geometrical interpretation of the Basel problem is given through the analogy of expanding circles and evenly spaced lighthouses, ultimately connecting this infinite series to geometry.

- 🤯 The final part of the solution involves adjusting the sum to account for even numbers by scaling the series, leading to the conclusion that the sum of all inverses of square numbers equals pi squared divided by 6.

Q & A

What is the Basel problem?

-The Basel problem involves summing the reciprocals of the squares of the positive integers. Mathematically, it is represented as: 1 + 1/4 + 1/9 + 1/16 + ... and asks what value this infinite series converges to.

How long did the Basel problem remain unsolved, and who solved it?

-The Basel problem remained unsolved for 90 years until Euler solved it in the 18th century, revealing that the sum of the series is equal to pi squared divided by 6 (π²/6).

Why is the result of the Basel problem surprising?

-The result is surprising because pi (π) is typically associated with circles, but here it appears in an unexpected context involving the sum of fractions. The connection between geometry and the series is not immediately apparent.

What is the inverse square law, and why is it important in the Basel problem?

-The inverse square law states that the intensity (or brightness) of a light source decreases in proportion to the square of the distance from the source. In the context of the Basel problem, the diminishing brightness of lighthouses positioned along the number line follows this law, which provides a geometric representation for the sum of the series.

How do the lighthouses in the script represent the sum of the reciprocals of squares?

-Each lighthouse represents a positive integer, and its brightness is inversely proportional to the square of its distance from the observer. The sum of the apparent brightnesses from all the lighthouses corresponds to the sum of the reciprocals of the squares of the integers.

What role does the inverse Pythagorean theorem play in the solution?

-The inverse Pythagorean theorem allows the transformation of a single lighthouse into two others without changing the total brightness. This transformation is key in manipulating the setup to create a solvable version of the Basel problem.

How does the script connect the Basel problem to geometry and circles?

-The script frames the problem geometrically by imagining lighthouses positioned around ever-larger circles. As the circles grow, the lighthouses are transformed through geometric constructions, and the sum of their brightnesses remains constant, ultimately leading to the discovery that the sum is π²/6.

Why is the sum of the series expressed as π²/6?

-The sum of the series is expressed as π²/6 because, after applying the geometric transformations and the inverse square law, the total brightness observed from the lighthouses corresponds to this formula, which Euler discovered in his solution to the Basel problem.

What happens when the series is restricted to odd integers?

-When the series is restricted to the odd integers, the sum is π²/8. This sum is a part of the full series and highlights the geometric manipulation that is required to transition between the series of odd and all positive integers.

How do the even integers factor into the final solution to the Basel problem?

-The series over the even integers is a scaled version of the full series, with each term being one-fourth of the corresponding term in the full series. By adjusting for this scaling factor, Euler connects the sum of the odd integers to the full series, ultimately leading to the sum being π²/6.

Outlines

This section is available to paid users only. Please upgrade to access this part.

Upgrade NowMindmap

This section is available to paid users only. Please upgrade to access this part.

Upgrade NowKeywords

This section is available to paid users only. Please upgrade to access this part.

Upgrade NowHighlights

This section is available to paid users only. Please upgrade to access this part.

Upgrade NowTranscripts

This section is available to paid users only. Please upgrade to access this part.

Upgrade NowBrowse More Related Video

The 5 Whys of Problem-Solving Method

Impossible Geometry Problems: Trisecting Angle, Doubling Cube, Squaring Circle

Why a "least squares regression line" is called that...

Cara Jawab Pertanyaan Interview: Apa Alasan Anda Melamar Di sini?

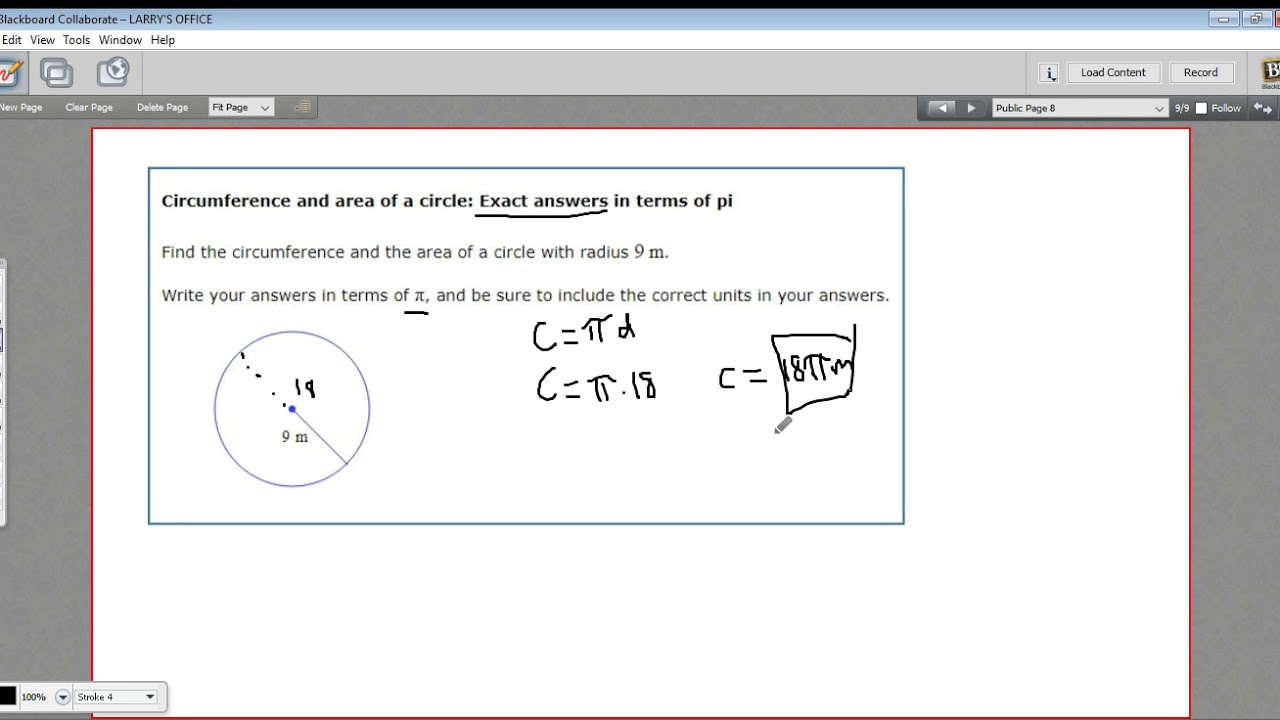

Circumference and area of a circle - exact answers in terms of pi

How to Answer: Tell Me About Yourself.

The 5 Why's Explained | Root Cause Analysis | Quality Management Certification | Invensis Learning

5.0 / 5 (0 votes)