The Island of Huge Hamsters and Giant Owls

Summary

TLDRThis script delves into the intriguing phenomenon of insular gigantism and dwarfism, as evidenced by the late Miocene epoch's Mikrotia fauna of Mediterranean islands. It narrates the evolutionary journey of these 'odd little giants', from their isolation on islands leading to significant size changes, to their eventual extinction due to rising sea levels. The script highlights the real-life powers of natural selection, showcasing creatures like the giant Deinogalerix and the enormous birds of prey, illustrating how island environments can dramatically alter species over time.

Takeaways

- 🌊 Greek and Roman mythologies are filled with tales of exotic islands inhabited by strange and terrifying creatures.

- 🐾 In the late Miocene epoch, there were real islands in the Mediterranean Sea with unusual, large-sized animals.

- 🏝️ The island animals were considered giants compared to their mainland ancestors but were actually small by today's standards.

- 🔍 Geographic isolation can lead to the evolution of new species with unusual sizes, both larger and smaller than their ancestors.

- 🇮🇹 In 1969, Dutch paleontologists discovered a rich fossil deposit in Gargano, Italy, revealing the existence of the Mikrotia fauna.

- 🦉 The Mikrotia fauna included oversized owls, hamsters, and hedgehogs, which were different from their mainland counterparts.

- 🌱 The absence of large predators and competitors on the islands allowed for the development of insular gigantism in some species.

- 🔄 Foster's Rule, identified by J. Bristol Foster, states that isolated environments often see large animals getting smaller and small animals getting larger.

- 🦔 Deinogalerix, a hedgehog-like creature, evolved from a small insectivore to a larger predator capable of hunting larger prey.

- 🦅 Large birds of prey, such as Tyto gigantea and Garganoaetus, evolved on the islands, possibly due to an evolutionary arms race with larger prey.

- 🌊 The extinction of the Mikrotia fauna is likely due to rising sea levels that reduced their island habitats, leading to their inability to adapt.

Q & A

What was the significance of the Mediterranean islands during the late Miocene epoch?

-The Mediterranean islands during the late Miocene epoch were significant because they were home to a unique group of animals that had evolved to be either much larger or smaller than their mainland counterparts due to geographic isolation. This phenomenon is a result of natural selection and is known as insular gigantism or insular dwarfism.

What is the Mikrotia fauna?

-The Mikrotia fauna refers to a group of animals found in the fossil deposits of the Gargano Peninsula and Scontrone in Italy. These animals were characterized by their unusually large or small body sizes compared to their mainland relatives, due to the effects of insular gigantism and insular dwarfism.

What role did geographic isolation play in the evolution of the animals on the Mediterranean islands?

-Geographic isolation played a crucial role in the evolution of the animals on the Mediterranean islands by allowing them to evolve independently from their mainland counterparts. This isolation led to the development of new species with unusual sizes, either much larger or smaller, due to the absence of predators, competitors, or other ecological pressures.

What is Foster’s Rule, and how does it relate to the animals of the Mikrotia fauna?

-Foster’s Rule, identified by biologist J. Bristol Foster in 1964, states that in isolated environments, large animals frequently get smaller, and tiny animals often become larger. This rule is exemplified by the Mikrotia fauna, where some animals evolved to be much larger than their mainland relatives, while others became smaller.

What were some of the peculiar animals found in the Mikrotia fauna?

-Some of the peculiar animals found in the Mikrotia fauna include extra-large owls, alarmingly big hamsters, supersized hedgehogs, and large birds of prey like Tyto gigantea and Garganoaetus. There were also large herbivores like the Hoplitomeryx, which had saber-like fangs and five horns on their heads.

What was the impact of the rising sea levels on the Mikrotia fauna?

-The rising sea levels about 5.3 million years ago dramatically shrank the island habitats of the Mikrotia fauna, leading to their extinction. The islands were flooded, reducing the available resources and habitat, which likely contributed to the extinction of these unique animals.

How did the animals on the Mediterranean islands adapt to their new environments after becoming isolated?

-After becoming isolated on the Mediterranean islands, many animals started to follow different evolutionary paths. Some stayed small or even shrank, while others responded to the absence of large predators and competitors by getting much larger. This allowed them to exploit new ecological niches and resources that were unavailable on the mainland.

What is the significance of the discovery of the Mikrotia fauna fossils in the study of evolution?

-The discovery of the Mikrotia fauna fossils is significant in the study of evolution as it provides concrete evidence of how geographic isolation can lead to the development of new species with unusual body sizes. It illustrates the power of natural selection and the adaptability of species in response to their environments.

What was the role of the giant owl Tyto gigantea in the ecosystem of the Mediterranean islands?

-The giant owl Tyto gigantea likely played a significant role as a top predator in the ecosystem of the Mediterranean islands. Its large size and powerful beak would have allowed it to hunt and consume larger prey than its mainland counterparts, contributing to the balance of the island's food web.

How did the animals on the Mediterranean islands become isolated from the mainland?

-The animals on the Mediterranean islands became isolated from the mainland due to changes in sea levels. During periods of lower sea levels, land bridges connected the islands to the mainland, allowing animals to migrate. However, as sea levels rose, these land bridges were submerged, turning the high spots into islands and cutting off the connection to the mainland.

Outlines

Cette section est réservée aux utilisateurs payants. Améliorez votre compte pour accéder à cette section.

Améliorer maintenantMindmap

Cette section est réservée aux utilisateurs payants. Améliorez votre compte pour accéder à cette section.

Améliorer maintenantKeywords

Cette section est réservée aux utilisateurs payants. Améliorez votre compte pour accéder à cette section.

Améliorer maintenantHighlights

Cette section est réservée aux utilisateurs payants. Améliorez votre compte pour accéder à cette section.

Améliorer maintenantTranscripts

Cette section est réservée aux utilisateurs payants. Améliorez votre compte pour accéder à cette section.

Améliorer maintenantVoir Plus de Vidéos Connexes

The Island of Shrinking Mammoths

That Time the Mediterranean Sea Disappeared

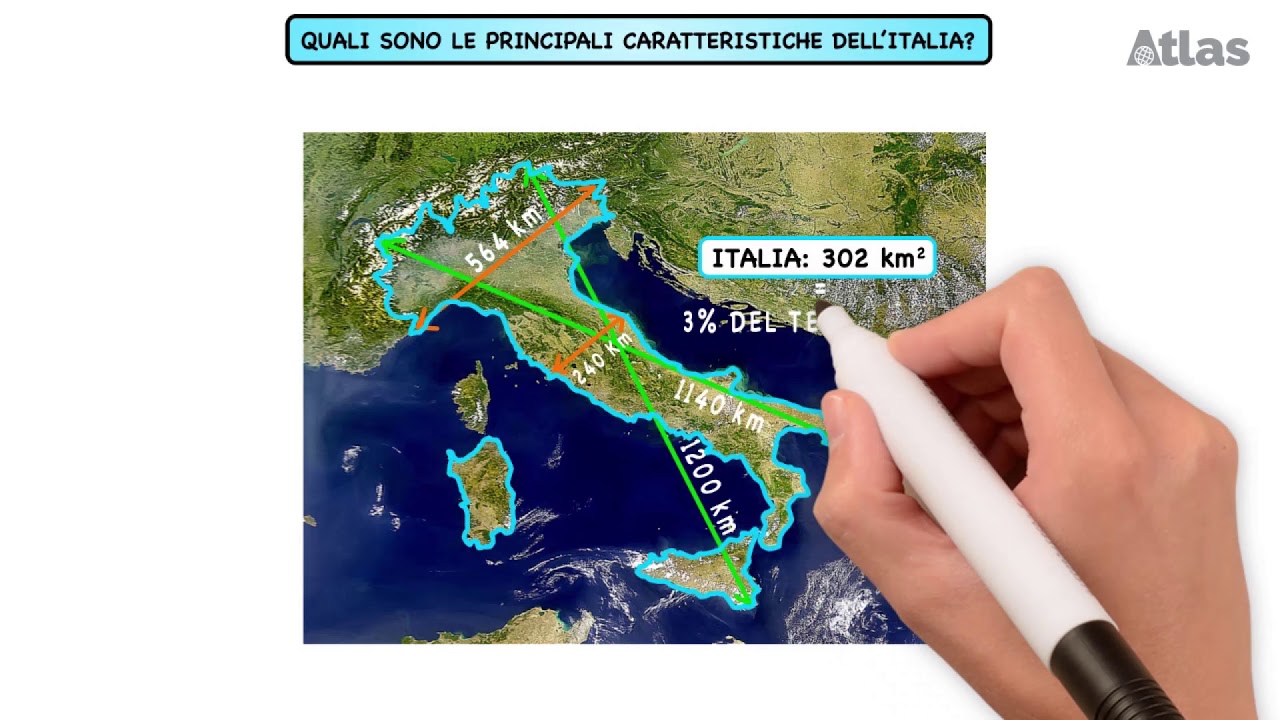

L'Italia, una terra a forma di stivale

Control and Coordination Class 10 Full Chapter (Animation) | Class 10 Science NCERT Chapter 7 | CBSE

gangguan pada sistem endokrin/hormonal | biologi sma kelas 11 bab.sistem endokrin utbk

Mysteries of vernacular: Pants - Jessica Oreck

5.0 / 5 (0 votes)