How to Solve the World’s Biggest Problems | Natalie Cargill | TED

Summary

TLDRThe speaker shares the story of Norman Borlaug and the Green Revolution, emphasizing how philanthropy can solve global challenges, from famine to pandemics. Highlighting philanthropy’s potential, she explores its transformative power, showing how investment in science, clean energy, and health could tackle critical global issues. With a thought experiment, the speaker suggests how even a small contribution from the world’s wealthiest could generate trillions of dollars, drastically improving poverty, pandemics, and climate change. The talk urges the audience to rethink the potential of philanthropy to create meaningful change.

Takeaways

- 🌾 The story of wheat and Norman Borlaug showcases how philanthropy helped revolutionize crop production, preventing a global famine and saving millions of lives.

- 💡 Philanthropy at its best can address problems that governments and markets are unable or unwilling to solve due to speed or risk factors.

- 🎖️ Norman Borlaug’s innovations in wheat farming led to the Green Revolution, significantly increasing global cereal production and earning him the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970.

- 💸 If the top 1% of global earners gave just 10% of their income, or 2.5% of their net worth, it could generate $3.5 trillion for global philanthropic efforts, in addition to the $1 trillion already given.

- 🌍 Global inequality is extreme, with individuals earning over $60,000 annually being part of the global 1%, highlighting the potential for redistributing wealth.

- 💧 For $260 billion, extreme poverty could be alleviated for a year through direct cash transfers, which have been proven to work better than many traditional aid interventions.

- 🦠 A $300 billion investment could help prevent the next pandemic by improving global biosecurity, vaccine distribution, and sanitation systems.

- 🌞 A clean energy sprint, backed by $840 billion, could double research and development into renewable energy, accelerating the fight against climate change.

- ⚛️ Nuclear risk is extremely high, and with just $2 billion, philanthropic efforts could significantly reduce the risk of nuclear disaster through better policies and systems.

- 🤖 Increasing AI safety funding by $1 billion could help mitigate the risks posed by increasingly powerful artificial intelligence, which currently lacks adequate safeguards.

Q & A

What story does the speaker share to introduce the potential of philanthropy?

-The speaker shares an anecdote about how philanthropists funded research that led to wheat innovations during the Green Revolution. This research, led by Norman Borlaug, helped increase wheat yields and potentially saved a billion lives by preventing mass famine.

Who was Norman Borlaug, and what was his contribution to agriculture?

-Norman Borlaug was a scientist who led a team working on wheat innovations during the Green Revolution. They developed high-yield, disease-resistant crops that helped prevent famine and dramatically increased global cereal production. For his contributions, Borlaug won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970.

How does the speaker describe philanthropy at its worst and at its best?

-At its worst, philanthropy is seen as a tool for the ultra-wealthy to manage their status or power without truly addressing what is needed. At its best, philanthropy is transformative, filling the gaps where governments and markets fail, as it did during the Green Revolution.

What role did philanthropic funding play in the Green Revolution?

-Philanthropic funding, particularly from the Rockefeller Foundation, provided the necessary resources to kickstart research into improving crop yields. Without this funding, governments and private investors, who were slower or unwilling to take risks, might have delayed such critical innovations.

What thought experiment does the speaker invite the audience to participate in?

-The speaker asks the audience to imagine themselves as philanthropists with a massive pile of cash, tackling some of the world's biggest and most solvable problems, like extreme poverty, pandemics, and climate change, using transformative philanthropy.

How much money does the speaker propose could be raised if the global top 1% gave a portion of their income?

-The speaker suggests that if the global top 1% of earners gave 10% of their income, or 2.5% of their net worth if they were particularly wealthy, it could raise an additional $3.5 trillion annually to improve the world.

What specific global problems could be addressed with the raised $3.5 trillion?

-With $3.5 trillion, we could address problems such as ending extreme poverty, reducing the risk of pandemics, doubling clean energy research, eradicating neglected tropical diseases, ending hunger, and suppressing nuclear risks, among others.

What are some solutions the speaker suggests to reduce the risk of future pandemics?

-The speaker suggests setting up sewage and wastewater screening programs to detect early signs of pandemics, upgrading labs for faster vaccine production, stockpiling PPE for essential workers globally, and investing in technologies like germicidal light to kill airborne viruses.

Why does the speaker emphasize the importance of funding clean energy research?

-The speaker emphasizes that clean energy research has already led to significant cost reductions in wind and solar power. Doubling investments in research could accelerate breakthroughs in other areas like nuclear and geothermal energy, as well as carbon capture and storage, helping to mitigate climate change.

What organizations does the speaker recommend for people interested in making effective philanthropic donations?

-The speaker recommends organizations like GiveDirectly, which provides direct cash transfers to the world's poorest people, and GiveWell, which evaluates global health interventions to identify the most effective charities. They also mention Longview Philanthropy's resources for further research.

Outlines

Dieser Bereich ist nur für Premium-Benutzer verfügbar. Bitte führen Sie ein Upgrade durch, um auf diesen Abschnitt zuzugreifen.

Upgrade durchführenMindmap

Dieser Bereich ist nur für Premium-Benutzer verfügbar. Bitte führen Sie ein Upgrade durch, um auf diesen Abschnitt zuzugreifen.

Upgrade durchführenKeywords

Dieser Bereich ist nur für Premium-Benutzer verfügbar. Bitte führen Sie ein Upgrade durch, um auf diesen Abschnitt zuzugreifen.

Upgrade durchführenHighlights

Dieser Bereich ist nur für Premium-Benutzer verfügbar. Bitte führen Sie ein Upgrade durch, um auf diesen Abschnitt zuzugreifen.

Upgrade durchführenTranscripts

Dieser Bereich ist nur für Premium-Benutzer verfügbar. Bitte führen Sie ein Upgrade durch, um auf diesen Abschnitt zuzugreifen.

Upgrade durchführenWeitere ähnliche Videos ansehen

The Green Revolution [AP Human Geography Unit 5 Topic 5]

Norman Borlaug & The Green Revolution

The Green Revolution in India | Transforming Agriculture and Food Production (1960s)

How the Green Revolution Changed the World [AP Human Geography Unit 5 Topic 5]

Professor Stuart Hart, Keynote June 2, 2011

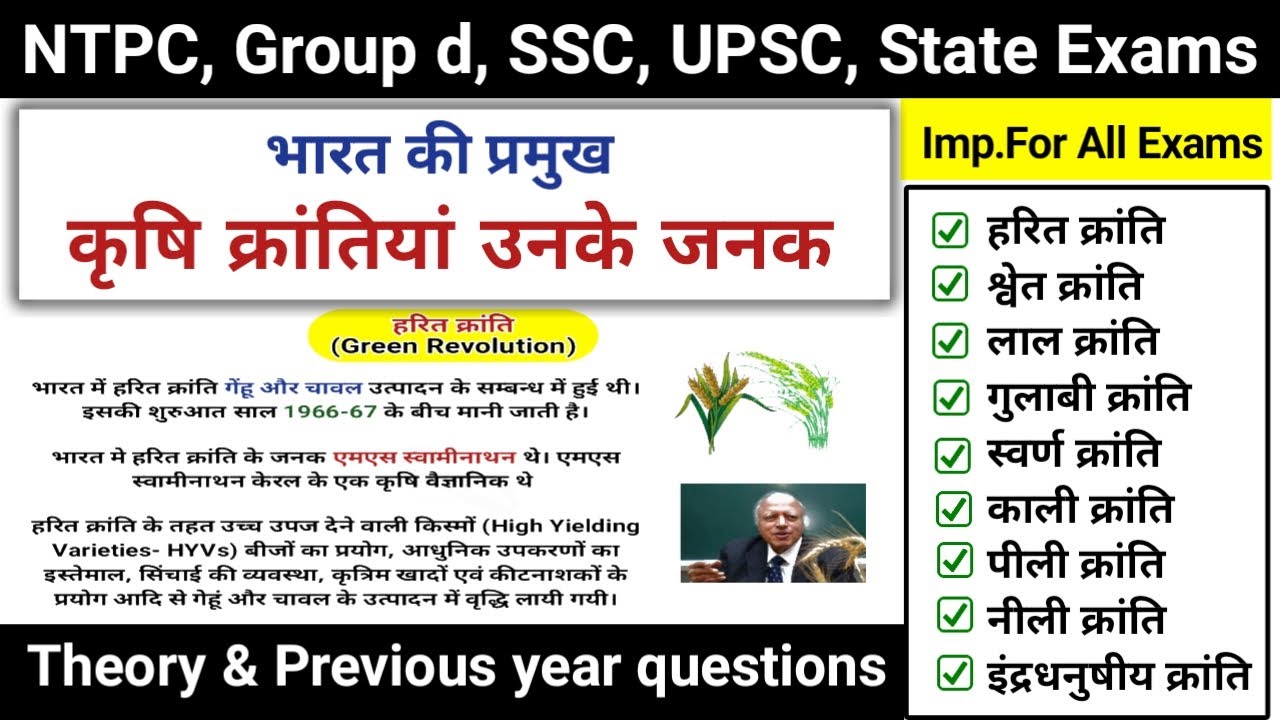

कृषि क्रांतियां | कृषि क्रांतियां और उनके जनक | agricultural revolution | study vines official

5.0 / 5 (0 votes)