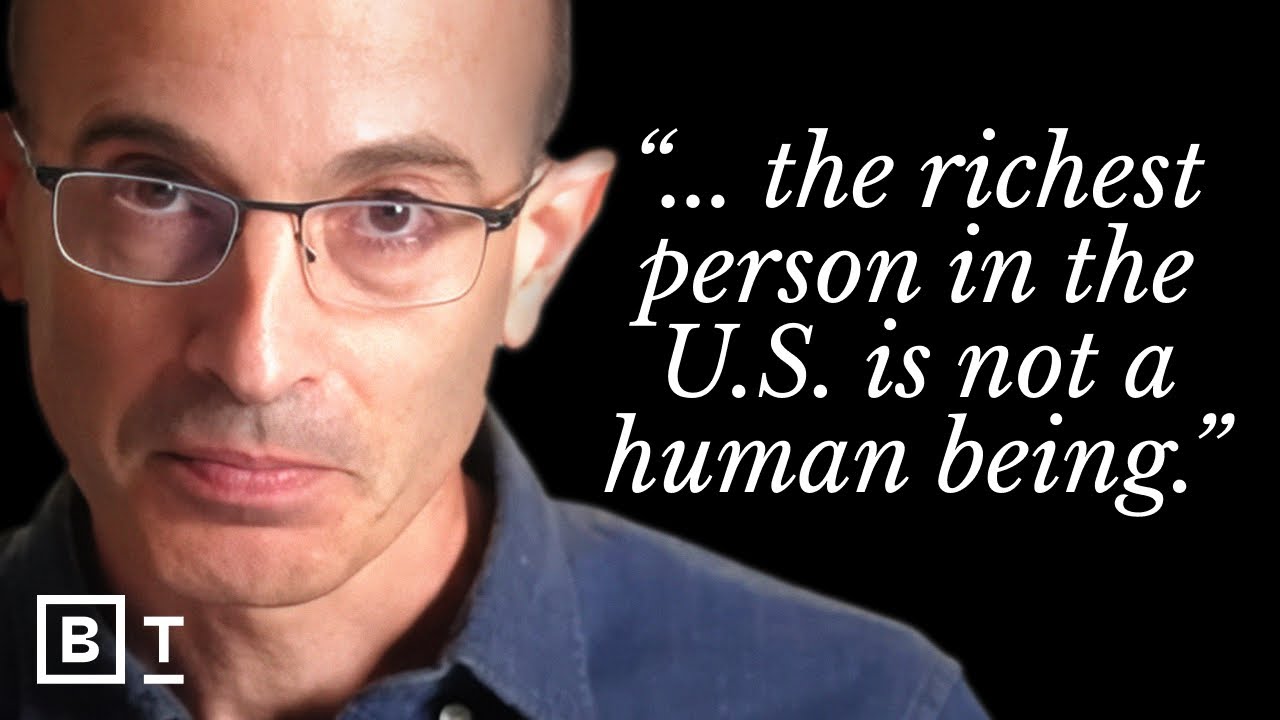

Why humans run the world | Yuval Noah Harari | TED

Summary

TLDRIn this thought-provoking talk, Yuval Noah Harari explores how humans evolved from insignificant animals to rulers of the planet through their unique ability to cooperate flexibly in large numbers. He highlights the power of shared beliefs in fictional stories, such as religion, human rights, and money, which enable mass cooperation. Harari also warns of future challenges, like technological advancements creating new social classes and potential inequalities. Ultimately, he questions humanity's purpose in a world where machines might surpass human capabilities.

Takeaways

- 🐒 Seventy-thousand years ago, humans were insignificant animals with minimal impact on the world.

- 🌍 Today, humans control the planet due to their unique ability to cooperate flexibly in large numbers.

- 🙊 Unlike social insects and mammals, humans can adapt their cooperation to new opportunities and threats.

- 💡 Human cooperation is based on shared beliefs in fictional stories, enabling large-scale collaboration.

- 📚 Fictional entities like gods, nations, money, and corporations underpin human societies and economies.

- 👥 Collective belief in stories like human rights and legal systems facilitates complex societal structures.

- 🦍 On an individual level, humans are not significantly different from chimpanzees, but they excel collectively.

- 💬 Human language allows the creation and dissemination of fictional realities, unlike other animals.

- 🛠️ Major human achievements, from building pyramids to moon landings, rely on mass cooperation.

- 🔮 Future challenges may include managing a new class of 'useless' people due to technological advancements.

Q & A

What is the main reason humans have come to control the planet?

-Humans control the planet because they are the only animals that can cooperate both flexibly and in very large numbers.

Why would a chimpanzee likely survive better than a human if they were placed together on a deserted island?

-On an individual level, humans are embarrassingly similar to chimpanzees, and in a survival scenario on a deserted island, a chimpanzee would likely survive better due to their natural abilities and instincts.

What sets human cooperation apart from that of other animals?

-Human cooperation is unique because it is both flexible and scalable, allowing humans to work together in large numbers and adapt to new situations quickly.

Why can't chimpanzees cooperate in large numbers like humans?

-Chimpanzees cannot cooperate in large numbers because their cooperation is based on intimate, personal knowledge of each other, which limits their ability to form large, cohesive groups.

How do humans use language differently from other animals?

-Humans use language not only to describe reality but also to create fictional realities. This ability to invent and believe in shared stories allows humans to cooperate on a massive scale.

Can you give an example of how humans use fictional stories to create cooperation?

-An example is religion, where millions of people can come together to build a cathedral or fight in a crusade because they believe in the same stories about God and heaven.

What are human rights according to the speaker?

-Human rights are fictional stories that humans have invented and spread. They are not an objective reality but rather a shared belief system that allows for large-scale cooperation.

What is the significance of money in human cooperation?

-Money is the most successful story ever invented because it is a universally accepted fiction. It allows people who do not know each other to trade and cooperate on a large scale.

Why does the speaker argue that the survival of rivers, trees, lions, and elephants depends on fictional entities?

-The survival of these natural elements depends on the decisions of fictional entities like nations, corporations, and international organizations, which exist only in human imagination but have real-world power.

What does the speaker predict about the future class struggles due to technological advancements?

-The speaker predicts that technological advancements, particularly in computing, may create a new class of 'useless people' as computers outperform humans in most tasks, leading to significant economic and social challenges.

How does the speaker view the concept of nations and states?

-The speaker views nations and states as fictional stories invented by humans. Unlike objective realities like mountains, nations and states exist because people collectively believe in them.

What is the speaker's perspective on economic inequality and future societal changes?

-The speaker believes that economic inequality is just beginning and that future societal changes may include the creation of biological castes with the rich becoming enhanced and the poor becoming increasingly marginalized.

Outlines

此内容仅限付费用户访问。 请升级后访问。

立即升级Mindmap

此内容仅限付费用户访问。 请升级后访问。

立即升级Keywords

此内容仅限付费用户访问。 请升级后访问。

立即升级Highlights

此内容仅限付费用户访问。 请升级后访问。

立即升级Transcripts

此内容仅限付费用户访问。 请升级后访问。

立即升级浏览更多相关视频

Why Humans Run the World - Yuval Noah Harari on TED

Bananas in heaven | Yuval Noah Harari | TEDxJaffa

AI, 2024 Elections & Fake Humans | Yuval Noah Harari on Morning Joe

Yuval Noah Harari: Why AI “gets us” and why it could ‘pick’ a president

Does Progress Actually Make You Happy? - [Sapiens Book Summary]

Stupidity: A powerful force in human history

5.0 / 5 (0 votes)