Chemistry of the Maillard Reaction

Summary

TLDRDieses Video erklärt die Myar-Reaktion, eine chemische Prozess, der dafür verantwortlich ist, dass Brot eine knuspere, braune Kruste und Steaks einen leckeren Sear bekommen. Es handelt sich um eine Art von nicht-enzymatischer Bräunung, die zwischen Aminosäuren, Proteinen und reduzierenden Zuckern stattfindet. Der Prozess ist temperaturabhängig und kann bei zu hohen Temperaturen schädliche Acrylamid-Moleküle erzeugen. Eine Erhöhung der pH-Wert kann die Reaktion anregen, da sie die Nukleophilie der Aminosäuren erhöht. Die Myar-Reaktion ist für das Bräunen im Backen und Kochen von Lebensmitteln verantwortlich und führt zu den charakteristischen Aromen und Texturen.

Takeaways

- 🍞 Das Maillard-Reaktion ist eine nicht-enzymatische Bräunung, die bei der Verbrennung von Brot und dem Sezieren von Steaks auftritt.

- 🍎 Im Gegensatz dazu ist die enzymatische Bräunung, wie beim Schnitt einer Apfelscheibe, ein Prozess, der durch Enzyme verursacht wird.

- 🍬 Die Maillard-Reaktion findet zwischen Aminosäuren und Proteinen und reduzierenden Zuckern statt, was sie von der Karamellisierung unterscheidet, die ausschließlich aus Zuckermolekülen besteht.

- 🍬 Reduzierende Zucker müssen einen freien Aldehyd- oder Ketongruppe haben, um an der Maillard-Reaktion teilnehmen zu können.

- 🔁 Monosaccharide sind reduzierende Zucker, da sie in ihrer linearen Form entweder einen freien Aldehyd oder einen freien Keten haben.

- 🔗 Disaccharide wie Sucrose sind nicht reduzierend, da ihre Anomeric-Carbonate durch eine Glycosidbindung miteinander verbunden sind und daher nicht in eine lineare Form umgewandelt werden können.

- 🥛 Lactose hingegen ist reduzierend, da die Glycosidbindung an der 1-4 Position die Anomeric-Carbonate nicht blockiert.

- 🍖 Die Maillard-Reaktion beinhaltet die Reaktion von Aminosäuren mit reduzierenden Zuckern und führt zu einer Reihe von Zwischenprodukten und最終 zu aromatischen Verbindungen und Melanoidinen.

- 🔥 Die Maillard-Reaktion erfolgt bei Temperaturen zwischen 142-165 °C (285-330 °F), bei höheren Temperaturen kann jedoch Acrylamide, ein giftiges Molekül, gebildet werden.

- 🥔 Bei hohen Temperaturen, wie beim Kochen von Kartoffeln oder Getreide, ist die Bildung von Acrylamide wahrscheinlicher aufgrund der höheren Asparaginsäure-Gehalts.

- 🔄 Eine Erhöhung des pH-Wertes erhöht die Nukleophilität der Aminogruppe und fördert somit die Maillard-Reaktion, was zu einer stärkeren Bräunung führt.

- 🍞 Die Bräunung beim Backen von Brot ist hauptsächlich auf die Maillard-Reaktion zurückzuführen, auch wenn Brot hauptsächlich aus Kohlenhydraten besteht.

Q & A

Was ist die Maillard-Reaktion?

-Die Maillard-Reaktion ist eine Art von nichtenzymatischer Bräunung, die zwischen Aminosäuren und Proteinen sowie reduzierenden Zuckern stattfindet. Sie ist für das Entstehen von angenehmen Aromen und Farben in gebratenem Brot oder Steak verantwortlich.

Was unterscheidet die Maillard-Reaktion von der Enzymatischen Bräunung?

-Die enzymatische Bräunung, wie beim Schnitt einer Apfelscheibe oder Bananenschale, wird von Enzymen katalysiert. Die Maillard-Reaktion hingegen findet ohne Enzyme statt und beinhaltet die Reaktion zwischen Aminosäuren und reduzierenden Zuckern.

Was ist ein reduzierender Zucker?

-Ein reduzierender Zucker ist ein Zucker, der eine freie Aldehyd- oder Ketone-Gruppe besitzt. Diese Gruppe ist für die Fähigkeit des Zuckers, in der Maillard-Reaktion zu reagieren, notwendig.

Wie sieht die Struktur eines reduzierenden Zuckers in linearer Form aus?

-In der linearen Form, wie bei D-Glukose, ist die Aldehydgruppe frei und kann reagieren. Bei Ketosen, wie D-Fruktose, muss durch Tautomerie eine freie Aldehydgruppe erzeugt werden, um reduzierend zu sein.

Was ist die Bedeutung von Disacchariden in Bezug auf die Maillard-Reaktion?

-Disaccharide wie Sucrose sind nicht reduzierend, weil ihre anomerk gebundenen Kohlenstoffe keine freie Aldehyd- oder Ketone-Gruppe haben. Andere Disaccharide wie Lactose sind reduzierend, da ihre anomerk gebundenen Kohlenstoffe in der Lage sind, in eine lineare Form zu isomerisieren, die eine freie reduzierende Gruppe enthält.

Was sind Aminosäuren und wie sind sie in Proteine aufgebaut?

-Aminosäuren bestehen aus einer Aminogruppe, einer Sauerstoffgruppe und einem variablen R-Gruppen. Durch Verketten mehrerer Aminosäuren entstehen Proteine.

Wie beginnt die Maillard-Reaktion?

-Die Maillard-Reaktion beginnt mit einer nukleophilen Angriff der Stickstoff-Atome der Aminogruppe auf das Carbonyl-Kohlenstoff der reduzierenden Zucker. Dies führt zu einer Reihe von Intermediaten und schließlich zu einer Amid-Bindung.

Was ist ein Amidori-Umlagerung?

-Eine Amidori-Umlagerung ist ein Prozess, bei dem aus einer Amid-Bindung ein Stickstoff mit einem C=C-Doppelbindung entsteht. Dies ist ein Vorgang in der Maillard-Reaktion, der zu größeren Molekülen und Melanoidinen führt.

Welche Temperaturen sind für die Maillard-Reaktion optimal?

-Die Maillard-Reaktion findet optimal bei Temperaturen von 142-165°C (oder 285-330°F) statt. Bei höheren Temperaturen kann Acrylamide gebildet werden, was giftig ist.

Was ist Acrylamide und warum ist es problematisch?

-Acrylamide ist ein in der Maillard-Reaktion bei hohen Temperaturen gebildetes Molekül, das giftig und für den Verbraucher schädlich sein kann. Es entsteht durch Dekarboxylation und Reaktionen der Amid-Bindung.

Wie beeinflusst die pH-Wert die Maillard-Reaktion?

-Ein erhöhter pH-Wert erhöht die Nukleophilie der Aminogruppe und fördert somit die Maillard-Reaktion. Bei sehr niedrigen pH-Werten kann die Aminogruppe protoniert werden, was ihre Nukleophilie verringert und die Reaktion hemmt.

Welche Rolle spielt die Maillard-Reaktion im Brotbackprozess?

-Die Maillard-Reaktion ist für das Bräunen des Brotes verantwortlich. Obwohl Brot hauptsächlich aus Kohlenhydraten besteht, enthält es auch Proteine, insbesondere Gluten, das bei der Backtemperatur zur Maillard-Reaktion beiträgt.

Outlines

此内容仅限付费用户访问。 请升级后访问。

立即升级Mindmap

此内容仅限付费用户访问。 请升级后访问。

立即升级Keywords

此内容仅限付费用户访问。 请升级后访问。

立即升级Highlights

此内容仅限付费用户访问。 请升级后访问。

立即升级Transcripts

此内容仅限付费用户访问。 请升级后访问。

立即升级浏览更多相关视频

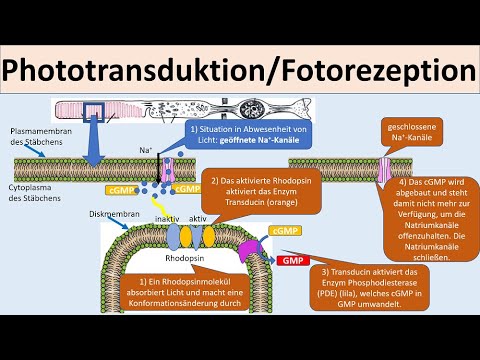

Phototransduktion/ Fotorezeption/ Signaltransduktion des Auges -[Neurobiologie, Oberstufe]

Was ist die Aktivierungsenergie?!

Proteinbiosynthese - Translation & Transkription - Abiturzusammenfassung Proteinbiosynthesen Genetik

HIGH PROTEIN CHEESECAKE (nur 3 Zutaten)

Zuschauerfrage: Was ist der Unterschied zwischen COPD und Asthma?

Wie funktioniert eine Batterie?

5.0 / 5 (0 votes)