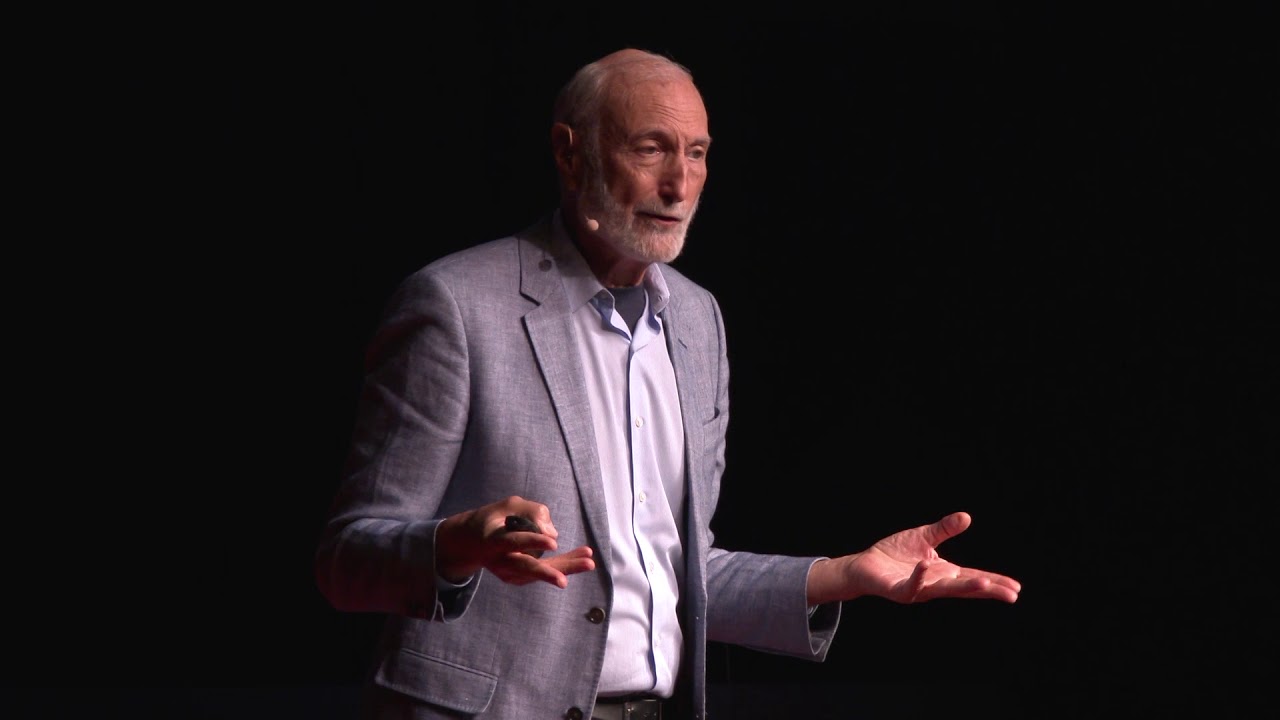

Feeling good | David Burns | TEDxReno

Summary

TLDRIn this powerful talk, Dr. David Burns discusses the impact of depression and anxiety, sharing his journey from a biological psychiatrist to adopting cognitive therapy. He explains the theory that negative thoughts create moods and how cognitive distortions contribute to mental health issues. Through his experiences and research, he demonstrates the effectiveness of cognitive therapy in treating depression, including his own personal application when facing his son's health crisis, ultimately emphasizing the potential for healing and happiness.

Takeaways

- 😔 Depression and anxiety are common and can be deeply distressing, with some individuals even praying for death as a preferable alternative to suicide.

- 🤔 The speaker initially pursued biological psychiatry, focusing on brain chemistry and the idea of chemical imbalances causing mental health issues, but found this approach insufficient.

- 💊 Antidepressants were prescribed extensively, but the speaker observed that they only helped a minority of patients, leading to a search for alternative treatments.

- 💡 The introduction of cognitive therapy by Aaron Beck offered a new perspective, suggesting that negative thoughts, not chemical imbalances, are the root of depression and anxiety.

- 🧠 Cognitive therapy is based on the idea that our thoughts create our moods, and by changing our thought patterns, we can change our emotional states.

- 🔍 The therapy identifies ten common distortions in thinking that contribute to negative emotions, such as all-or-nothing thinking and overgeneralization.

- 📚 The speaker's personal experience with cognitive therapy began skeptically but led to profound changes in his patients' lives, including those with long-term depression.

- 📈 Research has shown that cognitive therapy can be as effective, if not more so, than antidepressant medications for treating depression.

- 📖 The book 'Feeling Good' was written to provide tools and techniques from cognitive therapy to the general public, allowing self-help and acceleration of recovery.

- 🌟 The speaker's work and the development of cognitive therapy have led to significant advancements in the field of psychotherapy, making it the most researched form of therapy in history.

- 👨⚕️ The speaker's personal application of cognitive therapy techniques during a family crisis demonstrated their effectiveness and the importance of practicing what is preached.

Q & A

What is the main topic of the speaker's talk?

-The speaker's talk is focused on depression and anxiety, exploring their causes and potential treatments.

Why did the speaker initially believe in the chemical imbalance theory of depression and anxiety?

-The speaker initially believed in the chemical imbalance theory because he was a biological psychiatrist and was conducting research on brain chemistry at the time.

What were the two main problems the speaker faced with the chemical imbalance theory?

-The two main problems were that the speaker's own research did not confirm the chemical imbalance theory as the cause of depression and anxiety, and the fact that antidepressants were not helping most of his patients.

What is 'cognitive therapy' as mentioned in the script?

-Cognitive therapy is a form of psychotherapy developed by Aaron Beck, which posits that thoughts create all of our moods and that negative thoughts during depression and anxiety are distorted and not realistic.

What is the significance of the patient Martha's story in the script?

-Martha's story is significant as it illustrates the effectiveness of cognitive therapy. By challenging her negative thoughts, she was able to recognize her accomplishments and change her mood from depression to a more positive state.

What was the speaker's reaction to the idea of cognitive therapy initially?

-The speaker initially dismissed the idea of cognitive therapy as 'bullshit', doubting that it could help with serious cases of suicidal depression.

What did the speaker do after trying cognitive therapy with his first patient?

-After trying cognitive therapy with his first patient, the speaker began to see positive changes in his patients and decided to commit his life to this form of therapy, even returning a government grant to focus on it.

What is the role of the book 'Feeling Good' in the script?

-The book 'Feeling Good' is a manual written by the speaker for patients and the general public, providing tools and techniques of cognitive therapy to help people deal with depression and anxiety on their own.

What was the outcome of the research conducted at the University of Alabama regarding the book 'Feeling Good'?

-The research found that 69% of the patients who read 'Feeling Good' while on a waiting list for therapy recovered and did not need additional treatment.

How did the speaker apply cognitive therapy to his own life when his son was born with breathing difficulties?

-The speaker identified and challenged his own negative thoughts and distortions about his son's condition, which helped him to alleviate his anxiety and provide emotional support to his son.

What was the impact of the speaker's personal application of cognitive therapy on his son's condition?

-After the speaker calmed his own anxiety and provided emotional support to his son, the baby calmed down, started breathing, and was discharged from the intensive care unit.

Outlines

This section is available to paid users only. Please upgrade to access this part.

Upgrade NowMindmap

This section is available to paid users only. Please upgrade to access this part.

Upgrade NowKeywords

This section is available to paid users only. Please upgrade to access this part.

Upgrade NowHighlights

This section is available to paid users only. Please upgrade to access this part.

Upgrade NowTranscripts

This section is available to paid users only. Please upgrade to access this part.

Upgrade NowBrowse More Related Video

Imagine There Was No Stigma to Mental Illness | Dr. Jeffrey Lieberman | TEDxCharlottesville

The Most Powerful Strategy for Healing People and the Planet | Michael Klaper | TEDxTraverseCity

Stroke of insight - Jill Bolte Taylor

Mindfulness, the Mind, and Addictive Behavior - Judson Brewer

Myron Golden TEDx Talk The Master Key To Influence mp4

How to LOVE YOURSELF: three steps to overcoming self-hatred

5.0 / 5 (0 votes)