Land of the Long White Cloud | Episode 2: Inheriting Privilege | RNZ

Summary

TLDRThis script explores the complex identity of a Pākehā New Zealander, grappling with the historical injustices against Ngāi Tahu and the privilege of European descendants. It narrates a personal journey of understanding, beginning with the discovery of a great-great-grandfather's land acquisition through a race, to the realization of the need to educate and advocate for Māori rights and Te Tiriti o Waitangi. The speaker reflects on their own responsibility to challenge Pākehā norms and work towards a balanced society, acknowledging the material and cultural privileges that come with their heritage.

Takeaways

- 🏁 The speaker identifies as Pākehā, which refers to individuals of white European descent, particularly those with a history of colonization in New Zealand.

- 🏞️ By 1890, 90% of the Ngāi Tahu people were landless, a result of colonization and land dispossession.

- 🤝 The speaker's ancestors, Joseph and Bessy Doyle, had a positive relationship with Hori Kerei and Tini Kerei Taiaroa, indicating some level of support and understanding for Māori people.

- 🏅 The speaker's great-great-grandfather was known as a supporter of Māori representation in parliament, influenced by his friendship with Māori individuals.

- 🏆 The same ancestor won land in a running race, which was originally Ngāi Tahu land, highlighting the irony and complexity of his support for Māori rights.

- 📚 The speaker was not taught about Te Tiriti o Waitangi in school and felt a responsibility to educate others about its importance and the history of colonization.

- 🌐 The speaker emphasizes the importance of understanding the context of Māori history and the systems they had in place before colonization.

- 🔄 The concept of 'restoring balance' is presented as a way to honor Te Tiriti o Waitangi and to address historical injustices.

- 🚫 The speaker acknowledges the Pākehā privilege and the need for Pākehā to challenge their own patterns of thinking and understanding.

- 🏡 The speaker grew up on land that had a history of being taken from tangata whenua (indigenous people), without being aware of this history.

- 🌱 The speaker calls for personal responsibility in learning about one's ancestors, their history, and the ways they can contribute to a more balanced and just society.

Q & A

What was the situation of Ngāi Tahu by 1890 in terms of land ownership?

-By 1890, 90% of Ngāi Tahu were landless, meaning they either didn't have any land or didn't have enough land for economic survival.

What does the term 'Pākehā' refer to in the context of the script?

-In the script, 'Pākehā' refers to people of white European descent, particularly those of colonizer descent in New Zealand.

What is the speaker's perspective on their Pākehā identity?

-The speaker identifies as Pākehā and acknowledges it as a conflicted identity due to the historical context of colonization and the desire for a different history.

Who were Joseph and Bessy Doyle, and what was their relationship with Hori Kerei and Tini Kerei Taiaroa?

-Joseph and Bessy Doyle were the speaker's ancestors who had a positive relationship with Hori Kerei and Tini Kerei Taiaroa, Māori individuals with whom they shared a friendship and mutual support.

What was the significance of the speaker's great-great-grandfather being known as an outspoken supporter of Māori representation in parliament?

-The great-great-grandfather's support for Māori representation in parliament was significant as it was a positive stance during a time when Māori rights were being challenged, and it likely stemmed from his friendship with Hori Kerei Taiaroa.

How did the speaker's great-great-grandfather win land on the Canterbury Plains?

-The speaker's great-great-grandfather won land on the Canterbury Plains by being a good runner and winning a running race, which awarded him two parcels of land.

What was the speaker's reaction upon learning about Te Tiriti o Waitangi in a university paper?

-The speaker was upset and felt critical about not having learned about Te Tiriti o Waitangi earlier, reflecting on the importance of understanding the context of colonization and the treaty.

What is the speaker's view on the role of Pākehā in addressing historical injustices and honoring Te Tiriti o Waitangi?

-The speaker believes that Pākehā have a responsibility to understand their history, challenge their own patterns of thinking, and work towards restoring balance and honoring Te Tiriti o Waitangi without stepping out of their privilege.

What is the significance of the area named Doyleston?

-Doyleston was named after the speaker's great-great-grandfather who purchased the land there. It signifies the colonization and renaming of a place that had a history with tangata whenua.

What does the speaker suggest as a way to restore balance and work towards a healthier society in Aotearoa?

-The speaker suggests learning about one's ancestry, understanding the impact of colonization, and using personal influence within family and community to challenge thinking patterns and work towards honoring Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

What kind of privilege does the speaker acknowledge growing up on the Canterbury Plains?

-The speaker acknowledges the material privilege of growing up on stolen lands, as well as the privilege of cultural representation in school books and media, and the normalization of Pākehā ways of being.

Outlines

This section is available to paid users only. Please upgrade to access this part.

Upgrade NowMindmap

This section is available to paid users only. Please upgrade to access this part.

Upgrade NowKeywords

This section is available to paid users only. Please upgrade to access this part.

Upgrade NowHighlights

This section is available to paid users only. Please upgrade to access this part.

Upgrade NowTranscripts

This section is available to paid users only. Please upgrade to access this part.

Upgrade NowBrowse More Related Video

Mana: The power in knowing who you are | Tame Iti | TEDxAuckland

Identidad latinoamericana - Primera parte

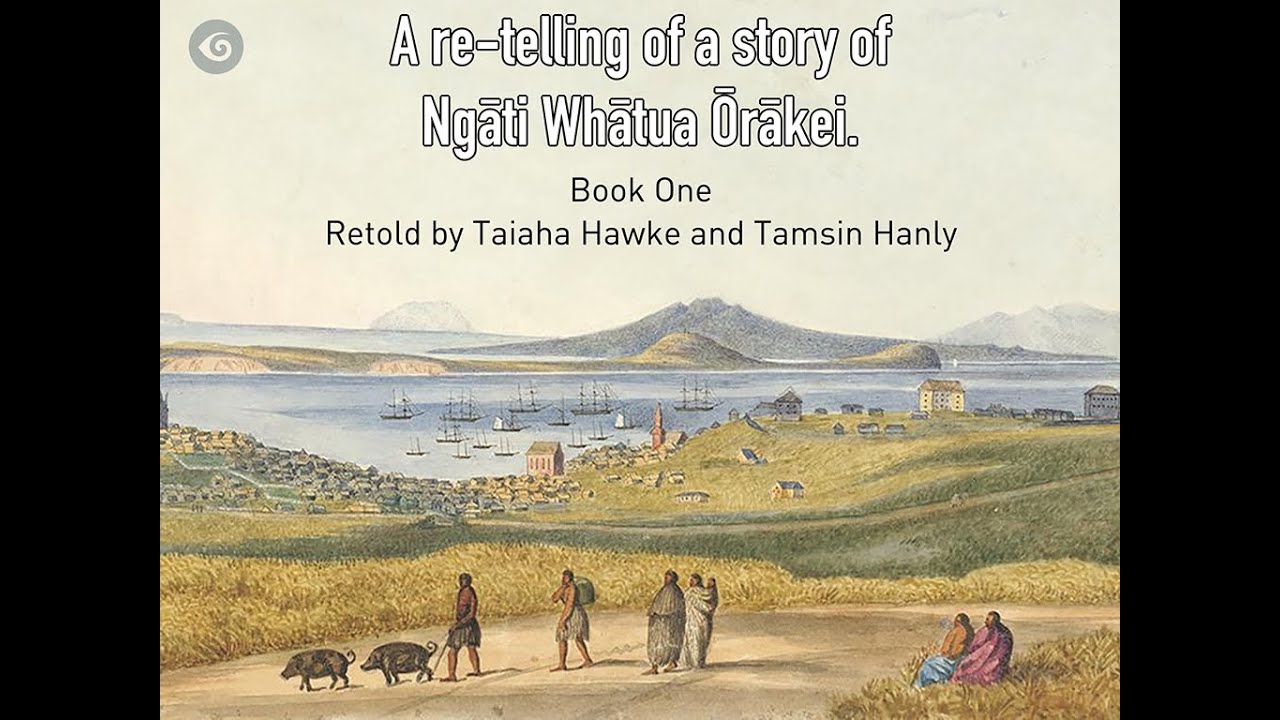

A retelling of a story of Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei (English Language version)

Mexican Americans are still fighting for land they were promised generations ago | Nightline

La historia de la Rebelión de los Comuneros (1781)

Why so many young Jews are turning on Israel | Simone Zimmerman | The Big Picture S4E7

5.0 / 5 (0 votes)