Connected, but alone? | Sherry Turkle

Summary

TLDRIn this talk, the speaker reflects on the evolution of technology and its impact on human relationships and self-reflection. She shares personal anecdotes and research findings to highlight how mobile devices and social media have changed our ways of communication, making us more connected yet more isolated. She emphasizes the need for meaningful conversations, solitude, and self-awareness in a tech-driven world. The speaker calls for a balanced relationship with technology, advocating for reclaiming real-life interactions and fostering genuine connections to enhance our well-being and community bonds.

Takeaways

- 📲 The speaker is both a technology enthusiast and a critic, highlighting the paradox of loving texts while recognizing their potential downsides.

- 👧 A personal anecdote about the speaker's daughter Rebecca sets the stage for discussing the evolution of technology and its impact on human relationships.

- 📚 The speaker's first TED Talk in 1996 celebrated the internet's potential for enhancing real-world identity and life, while her 2012 talk expresses concern about technology's unintended consequences.

- 📱 Mobile devices have become so ingrained in daily life that they change not just behaviors but also who we are as individuals.

- 🤳 People are increasingly multitasking with technology during what were once considered undivided attention activities, such as meetings, classes, and even funerals.

- 🔍 The speaker's research indicates a shift in how people relate to each other and themselves, with technology enabling a new kind of 'alone together' experience.

- 🤖 There's a growing desire for control in relationships, with people preferring to connect at a distance and on their own terms, which can hinder the development of face-to-face skills.

- 📝 The convenience of digital communication allows for self-presentation editing, which can lead to a preference for connection over real conversation and a loss of self-reflection.

- 🧑🦳 The illusion of companionship provided by technology, like social networks and sociable robots, is appealing but can be deceptive and emotionally unsatisfying.

- 🤔 The speaker calls for reflection on the role of technology in our lives, advocating for a more self-aware relationship with devices, others, and ourselves.

- 🌐 The script concludes with an optimistic outlook, emphasizing the importance of human connection and the potential for technology to enhance, rather than replace, real-life experiences.

Q & A

What was the speaker's initial perspective on the internet and virtual communities in 1996?

-The speaker was excited about the internet and virtual communities in 1996. She believed that what people learned about themselves in the virtual world could be used to improve their real-world lives.

How has the speaker's view on technology evolved since her first TED Talk?

-The speaker's view on technology has shifted from excitement to concern. She now believes that technology is taking us to places we don't want to go and that it's changing who we are, not just what we do.

What is the 'Goldilocks effect' mentioned in the script?

-The 'Goldilocks effect' refers to people's desire to have others at a distance they can control, neither too close nor too far, just right, reflecting the need for control over where they put their attention.

Why does the speaker find the use of technology during certain activities, like board meetings or funerals, concerning?

-The speaker is concerned because these activities are being interrupted by technology, which changes how we relate to each other and ourselves, and affects our capacity for self-reflection.

What does the speaker mean by 'we're setting ourselves up for trouble' in the context of technology use?

-The speaker implies that our reliance on technology for connection and distraction is causing issues in our relationships and self-reflection, potentially leading to isolation and a lack of genuine human interaction.

What is the speaker's view on the impact of texting and emailing on face-to-face relationships, especially among adolescents?

-The speaker believes that the reliance on texting and emailing can hinder the development of face-to-face relationships, which are crucial for adolescents, as they prefer controlled interactions over real conversations.

What does the speaker suggest is the appeal of technology in our lives?

-The speaker suggests that technology appeals to us where we are most vulnerable, offering illusions of companionship without the demands of friendship, and fulfilling our desires to be heard and not to be alone.

How does the speaker describe the shift in human relationships due to technology?

-The speaker describes a shift from rich, messy, and demanding human relationships to cleaner, more controlled interactions through technology, where people can edit and present themselves as they wish.

What is the 'I share therefore I am' concept mentioned by the speaker?

-'I share therefore I am' refers to the new way of defining ourselves through sharing thoughts and feelings on technology platforms, implying that our sense of self is now tied to our online presence and interactions.

What is the speaker's suggestion for a healthier relationship with technology?

-The speaker suggests developing a more self-aware relationship with technology, valuing solitude, reclaiming spaces for real conversation, and truly listening to each other, including the less exciting parts of communication.

What does the speaker call for at the end of the script?

-The speaker calls for reflection and a conversation about the impact of technology on our lives, urging us to reconsider how we use it and to focus on how it can lead us back to real-life connections and communities.

Outlines

This section is available to paid users only. Please upgrade to access this part.

Upgrade NowMindmap

This section is available to paid users only. Please upgrade to access this part.

Upgrade NowKeywords

This section is available to paid users only. Please upgrade to access this part.

Upgrade NowHighlights

This section is available to paid users only. Please upgrade to access this part.

Upgrade NowTranscripts

This section is available to paid users only. Please upgrade to access this part.

Upgrade NowBrowse More Related Video

Connected, but alone? - Sherry Turkle

CONNECTED, BUT ALONE? | Sherry Turkle (a summary-review)

Intel's cultural anthropologist talks life and technology

What is transhumanism? | Albert Lin | Storytellers Summit 2019

How do you keep up to date on everything technology has to offer? | Mike Saunders | TEDxGreshamPlace

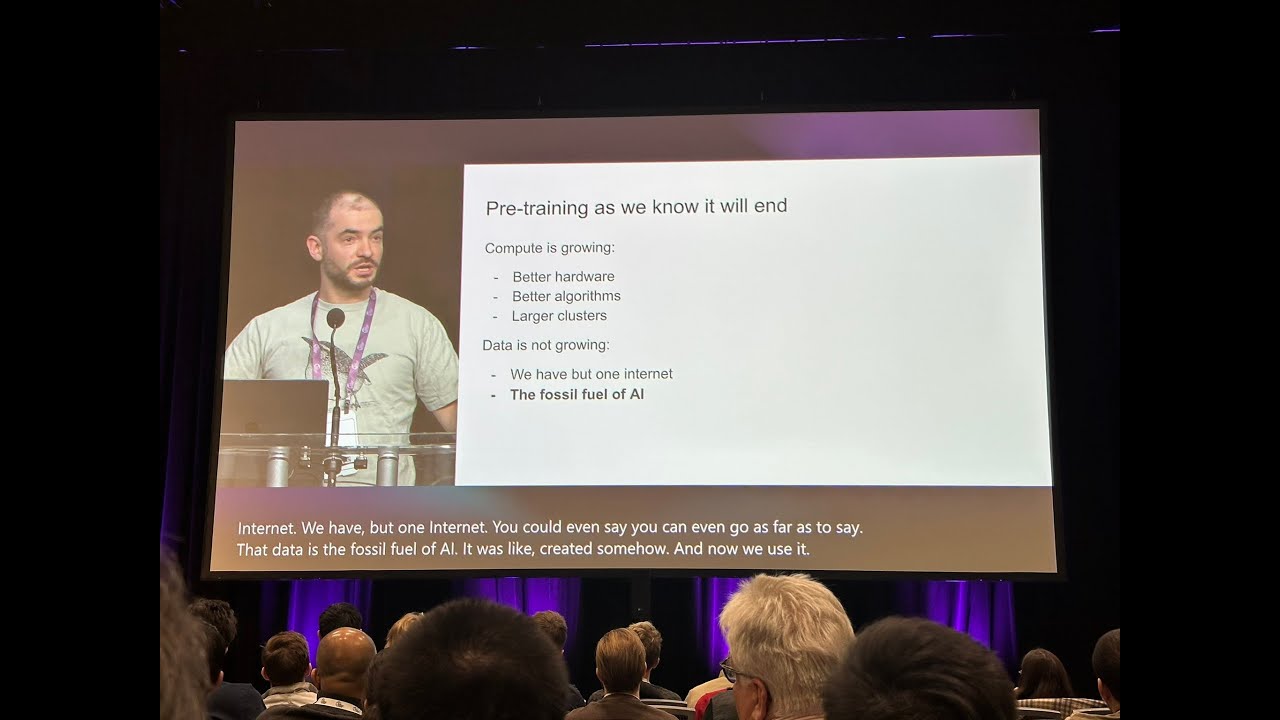

Ilya Sutskever: "Sequence to sequence learning with neural networks: what a decade"

5.0 / 5 (0 votes)