This "Dinosaur Egg" is One Of The Rarest Salts In The World | Still Standing | Insider Business

Summary

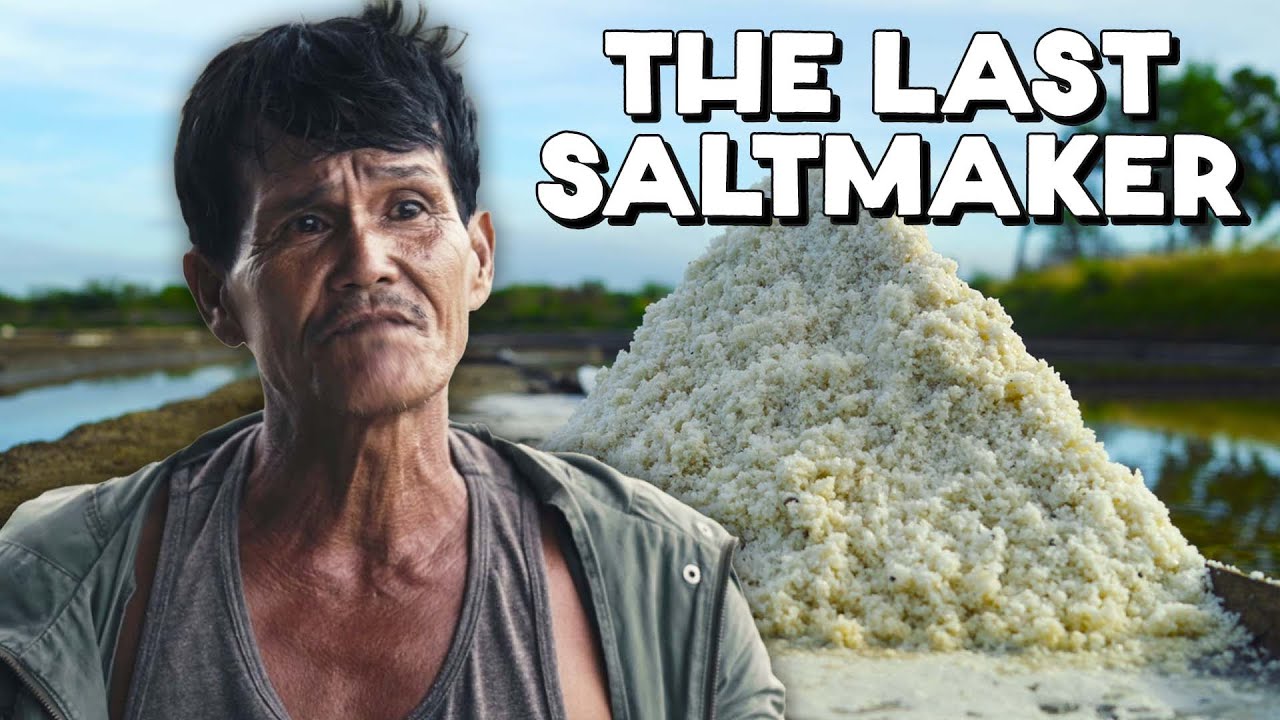

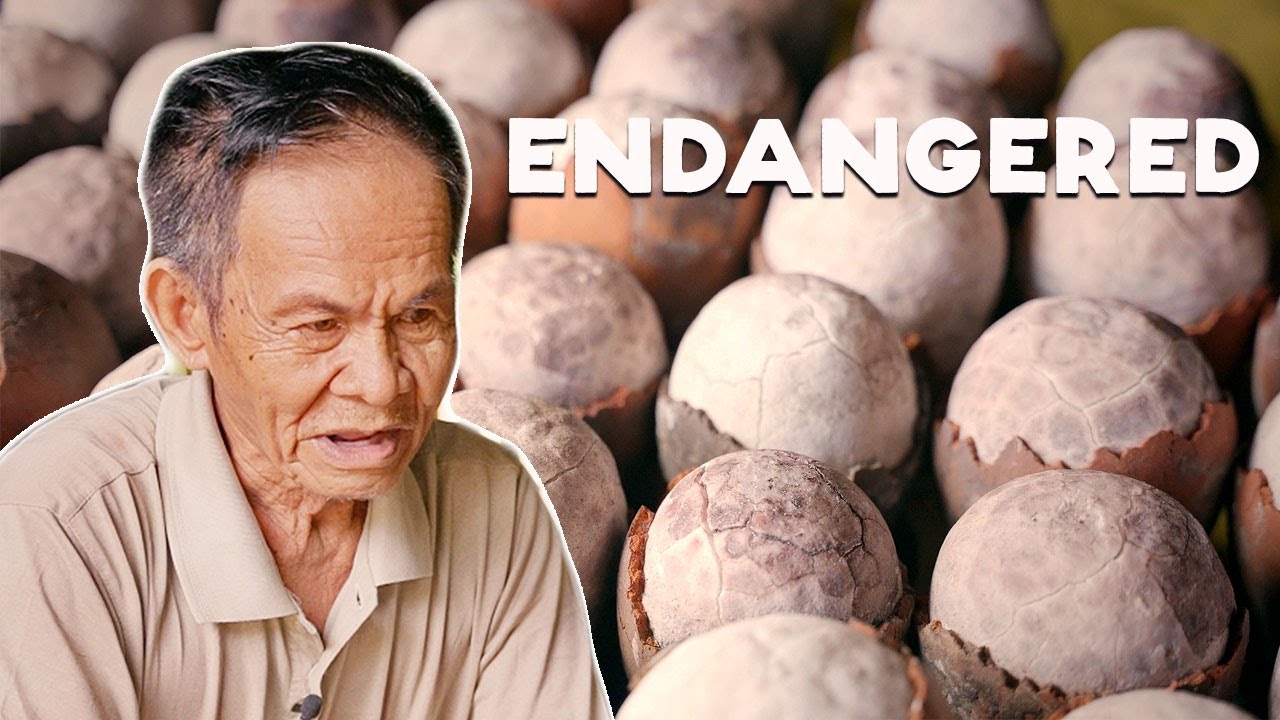

TLDRThe script narrates the story of asin tibuok, an artisanal salt known as 'dinosaur egg,' crafted by a few families on a small Philippine island. This rare salt, made from seawater brine and coconut husks, nearly vanished due to modernization but was revived by Nestor Manongas and his siblings. Despite a national law banning the sale of non-iodized salt, they persist, facing challenges like unpredictable weather and the need for new markets. The script also touches on the broader impact of similar laws on artisanal salt producers globally and the cultural significance of preserving this traditional craft.

Takeaways

- 🌊 The 'dinosaur egg' salt, or asin tibuok, is a rare artisanal salt made on a small island in the Philippines.

- ⏳ It requires eight hours of continuous cooking to produce this salt from seawater brine.

- 🏝️ In the 1960s, asin tibuok was used as a form of currency by families in Bohol, Philippines.

- 📉 The craft of making asin tibuok nearly vanished in the late 20th century due to younger generations seeking cash-paying jobs.

- 🔥 Nestor Manongas and his siblings revived the salt-making tradition 13 years ago, facing numerous challenges.

- 🚫 A national law in the Philippines bans the sale of non-iodized salt, making it difficult for traditional salt producers to sell their product within the country.

- 🌴 Coconut husks are a key ingredient that gives asin tibuok its unique taste and are used in the production process.

- 👥 Nestor's team of four, including adopted family members, carries out the labor-intensive salt-making process.

- 🍽️ Some restaurants, like Toyo Eatery in Manila, defy the iodized salt requirement to use asin tibuok for its culinary value.

- 🌍 The demand for asin tibuok is primarily from foreign customers and tourists, as local sales are restricted by law.

- 🏭 The 1995 ASIN law has led to a significant drop in national salt production and an increase in imported salt, impacting traditional salt makers.

Q & A

What is the name of the rare artisanal salt made on a small island in the Philippines?

-The rare artisanal salt is called asin tibuok.

How long does it take to transform seawater brine into asin tibuok?

-It takes eight hours of nonstop cooking to transform seawater brine into asin tibuok.

Why did the craft of making asin tibuok nearly disappear in the late 20th century?

-The craft nearly disappeared because younger people started favoring jobs that paid cash over traditional salt-making.

Who decided to revive the asin tibuok making tradition and when did they do it?

-Nestor Manongas and his siblings decided to revive the tradition 13 years ago.

What unique ingredient gives asin tibuok its distinct taste?

-Coconut husks are what give the salt its distinct taste.

How many coconut husks are needed to make one batch of asin tibuok?

-It takes 3,000 coconut husks to make one batch of asin tibuok.

What is the term for the pile of ashes left behind after burning the coconut husks?

-The pile of ashes left behind is called gasang.

What is the name of the rattan filter used in the salt-making process?

-The rattan filter used in the process is called sagsag.

What is the name of the salty brine that results from pumping seawater through the filter?

-The salty brine that results from pumping seawater through the filter is called tasik.

Why is it difficult for Nestor and his team to sell asin tibuok in their own country?

-A national law passed in 1995 requires all salt sold in the Philippines to be iodized, making it difficult for small-scale producers like Nestor to sell their traditional salt.

What is the name of the chef who uses asin tibuok in his award-winning restaurant in Manila?

-Chef Jordy Navarra uses asin tibuok in his restaurant, Toyo Eatery.

How does Nestor's team ensure the quality of their salt-making process?

-Nestor's team has strict rules before cooking begins, such as removing jewelry or watches and refraining from eating oily foods, based on superstitions passed down for generations.

Outlines

This section is available to paid users only. Please upgrade to access this part.

Upgrade NowMindmap

This section is available to paid users only. Please upgrade to access this part.

Upgrade NowKeywords

This section is available to paid users only. Please upgrade to access this part.

Upgrade NowHighlights

This section is available to paid users only. Please upgrade to access this part.

Upgrade NowTranscripts

This section is available to paid users only. Please upgrade to access this part.

Upgrade NowBrowse More Related Video

The Reality of Salt Making in the Philippines (Irasan Salt)

One of The Rarest Salt in the World is from the Philippines (Asin Tibuok)

Ang asin tibuok ng Bohol, paano nga ba ginagawa? | Pera Paraan

PENI UTAN LOLON - SMPN 2 ADONARA TIMUR

JURASSIC WORLD: REBIRTH | Official Telugu Trailer 1 (Universal Studios) - HD

MECAHIN TELUR DINOSAURUS MAHAL YANG ISINYA PULUHAN KEJUTAN!

5.0 / 5 (0 votes)