3 kinds of bias that shape your worldview | J. Marshall Shepherd

Summary

TLDRIn this engaging talk, a meteorologist with a PhD in physical meteorology humorously addresses common misconceptions about weather forecasting and climate change. He emphasizes the importance of understanding the difference between weather and climate, and critiques the public's skepticism towards climate science. The speaker discusses cognitive biases such as confirmation bias, the Dunning-Kruger effect, and cognitive dissonance, which contribute to the gap between scientific consensus and public perception. He advocates for expanding one's understanding by challenging personal biases, evaluating information sources, and speaking out about climate change.

Takeaways

- 🔮 Science is not a belief system; it is based on evidence, unlike beliefs such as the tooth fairy.

- 🌍 A significant gap exists between scientists and the public on various science topics, including climate change.

- 🤔 Belief systems and biases, such as confirmation bias, Dunning-Kruger effect, and cognitive dissonance, shape public perceptions of science.

- ❄️ Many people confuse weather with climate, leading to misconceptions, like using cold days to discredit global warming.

- 📊 Dunning-Kruger effect leads people to think they know more than they actually do, contributing to misinformed opinions.

- 🌀 Misinformation, especially in social media, distorts public understanding of scientific data, such as during Hurricane Irma.

- 🚨 Despite accurate weather forecasts, people struggle to accept predictions outside their experience, as seen with Hurricane Harvey.

- 🌡️ The media often amplifies incorrect perceptions, such as the misinterpretation of winter storm warnings during Atlanta's 'Snowpocalypse.'

- 🧠 To improve scientific literacy, individuals must take inventory of their biases and critically evaluate their information sources.

- 📢 Expanding one's understanding of science requires recognizing personal biases and openly discussing them, as exemplified by meteorologist Greg Fishel.

Q & A

What are the four common questions the speaker, Dr. Shepherd, receives as a meteorologist?

-The four common questions Dr. Shepherd receives are: 1) What channel is he on? 2) What's the weather going to be tomorrow? 3) Will it rain at someone's daughter's outdoor wedding next September? 4) Does he believe in climate change or global warming?

Why does Dr. Shepherd consider the question about believing in climate change as ill-posed?

-Dr. Shepherd considers the question about believing in climate change as ill-posed because science isn't a belief system. It's based on evidence and facts, not beliefs.

What is the difference between weather and climate according to Dr. Shepherd?

-Dr. Shepherd explains that weather is like your mood, which can change daily, while climate is like your personality, which is a long-term pattern of behavior.

What are the three elements that shape biases and perceptions about science according to Dr. Shepherd?

-The three elements that shape biases and perceptions about science according to Dr. Shepherd are confirmation bias, the Dunning-Kruger effect, and cognitive dissonance.

What is confirmation bias, and how does it relate to the public's understanding of climate change?

-Confirmation bias is the tendency to search for, interpret, favor, and recall information in a way that confirms one's preexisting beliefs or hypotheses. In the context of climate change, it means people may only pay attention to information that supports their view on the subject, ignoring scientific evidence to the contrary.

What is the Dunning-Kruger effect, and how does it apply to public understanding of scientific topics?

-The Dunning-Kruger effect is a cognitive bias where people with low ability at a task overestimate their ability, while those with high ability underestimate their competence. It applies to public understanding of scientific topics as people might think they understand more than they actually do, leading to misconceptions.

Can you explain cognitive dissonance as described by Dr. Shepherd?

-Cognitive dissonance, as described by Dr. Shepherd, is the mental discomfort experienced by a person who holds two or more contradictory beliefs, ideas, or values. He uses the example of people asking for a rodent's or Farmer's Almanac weather forecast despite more accurate scientific methods being available.

How does misinformation impact public perception of weather forecasts, as mentioned by Dr. Shepherd?

-Misinformation, such as fake weather forecasts or outdated methods like the Farmer's Almanac, can lead the public to distrust or ignore accurate scientific forecasts, impacting their preparedness for weather events.

What role does literacy play in shaping people's understanding of science, according to Dr. Shepherd?

-Literacy in science is crucial as it allows individuals to better understand and interpret scientific information. A lack of scientific literacy can lead to misunderstandings and perpetuation of biases and misinformation.

What did Dr. Shepherd predict about Hurricane Harvey before it made landfall?

-Dr. Shepherd predicted that Hurricane Harvey would bring 40 to 50 inches of rainfall a week before it made landfall.

What is the advice Dr. Shepherd gives to expand one's understanding of science?

-Dr. Shepherd advises taking inventory of one's own biases, evaluating the sources of scientific information, and speaking out about one's understanding and biases to expand one's radius of understanding of science.

Outlines

Dieser Bereich ist nur für Premium-Benutzer verfügbar. Bitte führen Sie ein Upgrade durch, um auf diesen Abschnitt zuzugreifen.

Upgrade durchführenMindmap

Dieser Bereich ist nur für Premium-Benutzer verfügbar. Bitte führen Sie ein Upgrade durch, um auf diesen Abschnitt zuzugreifen.

Upgrade durchführenKeywords

Dieser Bereich ist nur für Premium-Benutzer verfügbar. Bitte führen Sie ein Upgrade durch, um auf diesen Abschnitt zuzugreifen.

Upgrade durchführenHighlights

Dieser Bereich ist nur für Premium-Benutzer verfügbar. Bitte führen Sie ein Upgrade durch, um auf diesen Abschnitt zuzugreifen.

Upgrade durchführenTranscripts

Dieser Bereich ist nur für Premium-Benutzer verfügbar. Bitte führen Sie ein Upgrade durch, um auf diesen Abschnitt zuzugreifen.

Upgrade durchführenWeitere ähnliche Videos ansehen

Previsão do Tempo – Ciências – 8º ano – Ensino Fundamental

Inside the mind of a climate change scientist | Corinne Le Quéré | TEDxWarwick

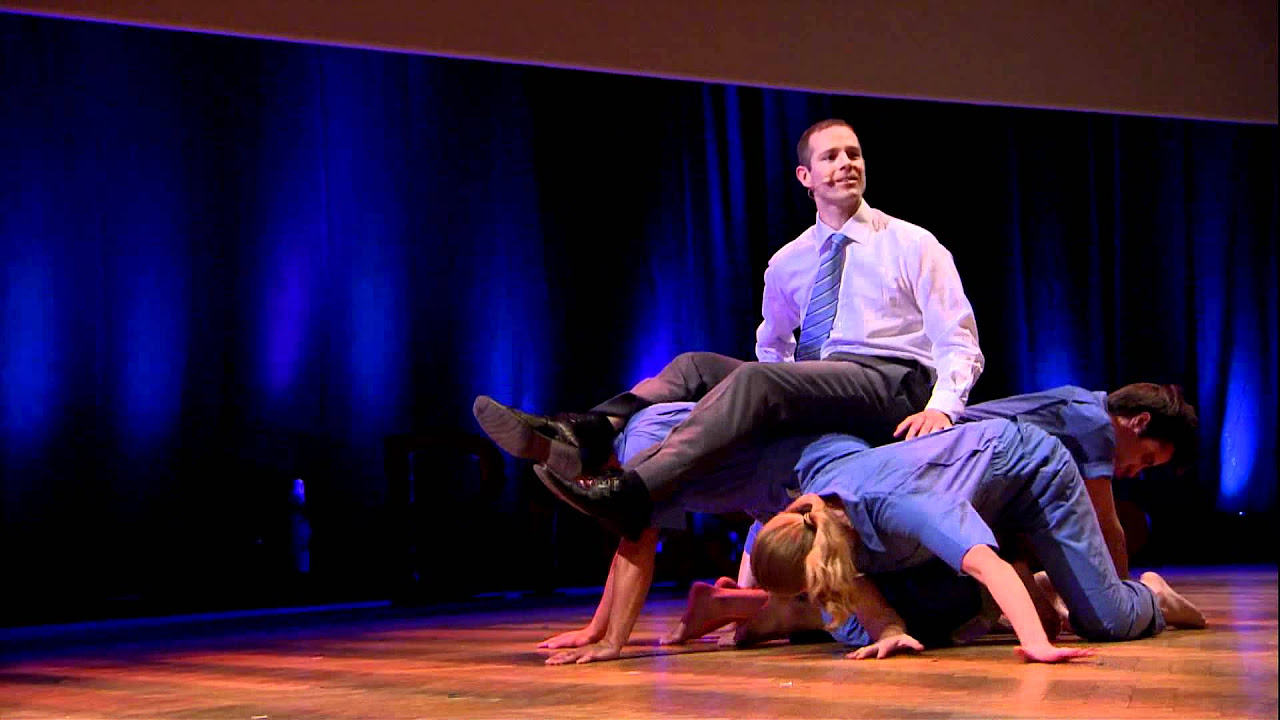

Dance your PhD | John Bohannon & Black Label Movement | TEDxBrussels

What are weather fronts and how do they affect our weather?

Everest Weather - Data is in the Clouds | National Geographic

Introduction to Meteorology

5.0 / 5 (0 votes)