The puzzle of motivation | Dan Pink | TED

Summary

TLDRThe speaker humorously confesses to attending law school and makes a compelling case for rethinking business practices. He discusses the candle problem to illustrate the limitations of extrinsic motivators like rewards and punishments, which can stifle creativity and hinder performance on complex tasks. Instead, he advocates for intrinsic motivation, focusing on autonomy, mastery, and purpose as the keys to high performance in the 21st century.

Takeaways

- 📚 The speaker admits to attending law school but not practicing law, setting a tone of humility and self-deprecation.

- 🔍 The 'candle problem' is introduced as a metaphor for overcoming 'functional fixedness' and thinking outside the box.

- 🏁 Sam Glucksberg's experiment is highlighted to illustrate the counterintuitive effect of incentives on problem-solving, where higher rewards can actually hinder performance.

- 💰 The speaker challenges the traditional business belief in the effectiveness of extrinsic motivators like bonuses and commissions.

- 🔬 The mismatch between scientific findings on motivation and current business practices is emphasized, suggesting that the latter are outdated.

- 🛠 The 20th-century business model, based on extrinsic motivators, is critiqued as ineffective for the creative and conceptual tasks of the 21st century.

- 🤔 The importance of intrinsic motivation for high performance in complex tasks is underscored, including autonomy, mastery, and purpose.

- 🌐 Examples of companies like Atlassian and Google are given to demonstrate the success of providing employees with autonomy in their work.

- 📈 The Results Only Work Environment (ROWE) is presented as an example where removing traditional work constraints leads to increased productivity and satisfaction.

- 🌐 The success of Wikipedia over Microsoft's Encarta is cited as a real-world example of the triumph of intrinsic motivation over extrinsic rewards.

- 🚀 The speaker concludes by advocating for a new business approach centered on intrinsic motivators to drive creativity, engagement, and ultimately, world change.

Q & A

What is the speaker's confession about their past?

-The speaker confesses to attending law school in the late 1980s, where they did not perform well academically and never practiced law professionally.

What is the candle problem and its significance in the speech?

-The candle problem is an experiment created by Karl Duncker in 1945 to illustrate the concept of functional fixedness. It is used in the speech to demonstrate the importance of creative thinking and the limitations of certain types of incentives.

What did Sam Glucksberg's experiment on the candle problem reveal about incentives?

-Glucksberg's experiment showed that offering financial incentives to solve the candle problem actually made participants take longer to find the solution, indicating that incentives can sometimes hinder creative problem-solving.

Why do traditional management practices and extrinsic motivators fail in the context of modern work?

-Traditional management practices and extrinsic motivators are less effective for modern work because they are better suited for simple, rule-based tasks. They do not foster the creativity and autonomy needed for complex, conceptual tasks that are common in the 21st century.

What are the three elements of a new operating system for businesses according to the speaker?

-The three elements are autonomy, mastery, and purpose. Autonomy is the urge to direct one's own life, mastery is the desire to improve at something meaningful, and purpose is the drive to contribute to something larger than oneself.

How does the Results Only Work Environment (ROWE) differ from traditional work environments?

-In a ROWE, employees do not have set schedules or mandatory office hours. They are given the freedom to complete their work as they see fit, which can lead to increased productivity, engagement, and satisfaction.

What is the significance of the comparison between Microsoft Encarta and Wikipedia?

-The comparison highlights the power of intrinsic motivation. Wikipedia, which is created by volunteers for the love of sharing knowledge, outperformed Encarta, which was a commercially driven project with financial incentives.

What is the '20% time' policy at Google, and how has it contributed to the company's innovation?

-The '20% time' policy allows Google engineers to spend 20% of their work time on projects of their own choosing. This policy has led to the creation of several successful products, such as Gmail and Google News.

How does the speaker define intrinsic motivation?

-Intrinsic motivation is defined by the speaker as the desire to do things for their own sake, because they matter, are interesting, or are part of something important, without the need for external rewards.

What is the main argument the speaker makes against the use of traditional extrinsic motivators in business?

-The speaker argues that traditional extrinsic motivators, such as bonuses and punishments, are outdated and can actually harm performance, especially in tasks that require creativity and conceptual thinking.

What does the speaker suggest as a solution to the mismatch between scientific knowledge and business practices?

-The speaker suggests adopting a new approach to motivation based on intrinsic factors such as autonomy, mastery, and purpose, which are more aligned with the needs of the 21st-century workplace.

Outlines

This section is available to paid users only. Please upgrade to access this part.

Upgrade NowMindmap

This section is available to paid users only. Please upgrade to access this part.

Upgrade NowKeywords

This section is available to paid users only. Please upgrade to access this part.

Upgrade NowHighlights

This section is available to paid users only. Please upgrade to access this part.

Upgrade NowTranscripts

This section is available to paid users only. Please upgrade to access this part.

Upgrade NowBrowse More Related Video

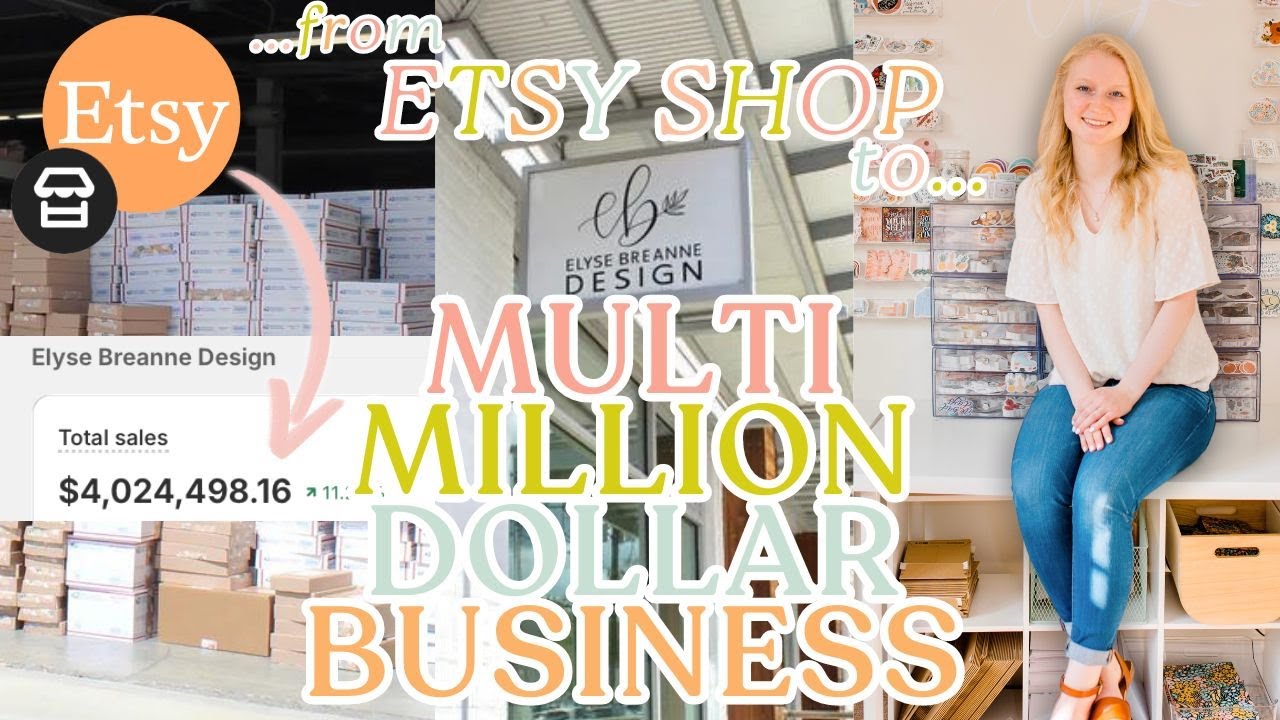

How I turned my small Etsy shop into a MULTI-MILLION dollar business!

Cak Lontong: Tidak semua orang yang korupsi itu koruptor

Estudo de Caso: Gestão de Pessoas e a Estratégia de Desempenho | Laura Widal

Global Ethics Forum: Ethics Matter: A Conversation with Dov Seidman

Why Network Marketing Is The Best Business Opportunity?

How Maritime Law Works

5.0 / 5 (0 votes)